Harem (pronounced [ha’?em], Turkish, from Arabic: ???? ?aram “forbidden place; sacrosanct, sanctum”, related to ???? ?ar?m, “a sacred inviolable place; female members of the family” and ???? ?ar?m, “forbidden; sacred”) refers to the sphere of women in what is usually a polygynous household and their enclosed quarters which are forbidden to men. The term originated with the Near East. Harems are composed of wives and concubines. For the South Asian equivalent, see purdah and zenana.

Etymology

The word has been recorded in the English language since 1634, via Turkish Harem, from Arabic ?aram “forbidden because sacred/important”, originally implying “women’s quarters”, literally “something forbidden or kept safe”, from the root of ?arama “to be forbidden; to exclude”. The triliteral ?-R-M is common to Arabic words denoting Forbidden. The word is a cognate of Hebrew ?erem, rendered in Greek as haremi (ha-re-mi) when it applies to excommunication pronounced by the Jewish Sanhedrin court; all these words mean that an object is “sacred” or “accursed”.

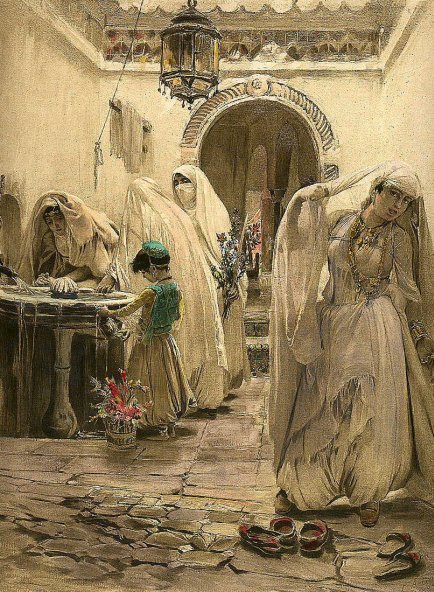

Female seclusion in Islam is emphasized to the extent that any unlawful breaking into that privacy is ?ar?m “forbidden”. A Muslim harem does not necessarily consist solely of women with whom the head of the household has sexual relations, but also their young offspring, other female relatives, etc. The Arabic word ???? ?urmah, plural ???? ?ar?m, was traditionally a term for a woman of the speaker’s family, regardless of status. It may either be a palatial complex, as in Romantic tales, in which case it includes staff (women and eunuchs), or simply their quarters, in the Ottoman tradition separated from the men’s selaml?k. The zenana was a comparable institution.

It is being more commonly acknowledged today that the purpose of harems during the Ottoman Empire was for the royal upbringing of the future wives of noble and royal men. These women would be educated so that they were able to appear in public as a royal wife.

History

The word Harem is strictly applicable to Muslim households only, but the system was common, more or less, to most ancient Oriental communities, especially where polygamy was permitted.

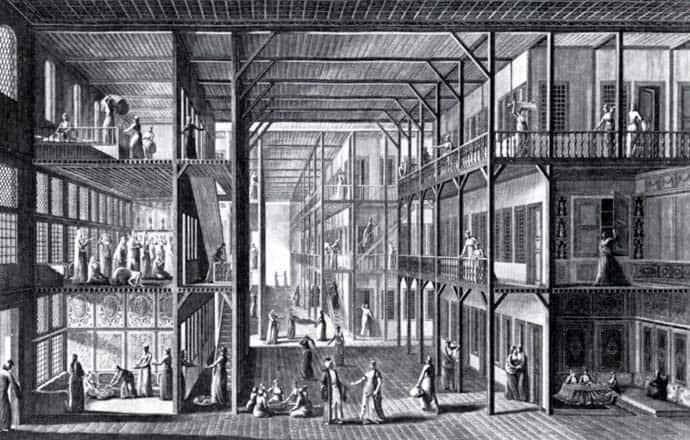

The Imperial Harem of the Ottoman sultan, which was also called seraglio in the West, typically housed several dozen women, including wives. It also housed the sultan’s mother, daughters and other female relatives, as well as eunuchs and slave servant girls to serve the aforementioned women. During the later periods, the sons of the sultan lived in the Harem until they were 12 years old, when it was considered appropriate for them to appear in the public and administrative areas of the palace. The Topkap? Harem was, in some senses, merely the private living quarters of the sultan and his family, within the palace complex. Some women of Ottoman harem, especially wives, mothers and sisters of sultans, played very important political roles in Ottoman history, and in times it was said that the empire was ruled from harem. Hürrem Sultan (wife of Suleiman the Magnificent, mother of Selim II), Nurbanu Sultan ( wife of Selim II, mother of Murad III) and Kösem Sultan (mother of Murad IV) were the three most powerful women in Ottoman history.

In the Ottoman period before Atatürk’s Reforms, “harem”, more properly (Turk.) haremlik, meant simply the private or family area of a typical upper-class household, as opposed to the public or reception rooms known as the selamlik.

Sultan Ibrahim the Mad, Ottoman ruler from 1640 to 1648, is said to have drowned 280 concubines of his harem in the Bosphorus. At least one of his concubines, Turhan Hatice, a Ukrainian who was captured during one of the raids by Tatars and sold into slavery, survived his reign.

The harem was not just a place where women lived. Babies were born and children grew up there. Within the precincts of the harem were markets, bazaars, laundries, kitchens, playgrounds, schools and baths. The harem had a hierarchy, its chief authorities being the wives and female relatives of the emperor and below them were the concubines. There was mother, step-mothers, aunts, grandmothers, step-sisters, sisters, daughters and other female relatives that lived in the harem. There were also ladies-in-waiting, servants, maids, cooks, women official and guards.

Outside Islamic culture

King Kashyapa of Sigiriya in Sri Lanka had as many as 500 women of the harem (Orodha). They are depicted in the Sigiriya Frescoes and referred to in graffiti on the Mirror Wall there. The harem consisted of concubines and female members of the royal court. It was considered an honour to be a “lady of the king’s harem”.

In Mexico, Aztec ruler Montezuma II, who met Cortes, kept 4,000 concubines; every member of the Aztec nobility was supposed to have had as many consorts as he could afford.

Harem is also the usual English translation of the Chinese language term hougong (hou-kung; Chinese: ??; literally: “the palace(s) behind”). Hougong refers to the large palaces for the Chinese emperor’s consorts, concubines, female attendants and eunuchs. The women who lived in an emperor’s hougong sometimes numbered in the thousands. In 1421, the Yongle Emperor ordered 2,800 concubines, servant girls and eunuchs who guarded them to a slow slicing death as the Emperor tried to suppress a sex scandal which threatened to humiliate him.

A similar institution existed among the ?oku during the Edo period in Japan.

Heshen had 600 women in his harem.

Some African royal and noble lineages also have long traditions of polygyny. During the colonization of Africa, the junior wives and concubines of the native chieftains were often collectively referred to as their harems by colonial officials. Although the ritually superior great wives in these cases — consorts in the traditionally Western sense who were often the earliest of them to have been married — were usually vested with powers that made them distinct when compared to their fellow spouses, they were often considered by the colonialists to be members of the harems. In modern African polygynous cases, as in that of the royal family of the King of Swaziland, the word is generally avoided due to socio-linguistic political correctness, although it is technically correct to refer to a group of women married to a single tribal chief in this manner.

Depictions in contemporaneous Western culture

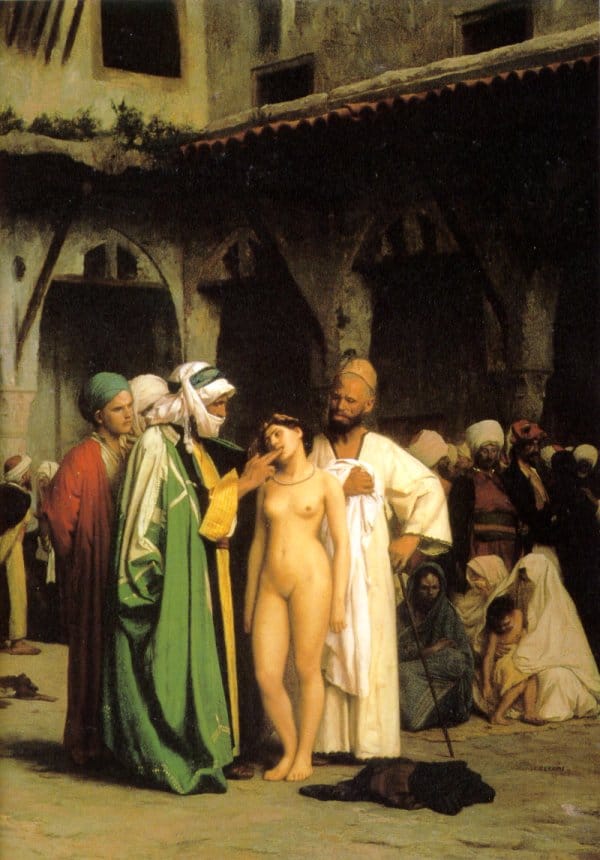

The institution of the harem exerted a certain fascination on the European imagination, especially during the Age of Romanticism, and was a central trope of Orientalism in the arts, due in part to the writings of the adventurer Richard Francis Burton. Many Westerners falsely imagined a harem as a brothel consisting of many sensual young women lying around pools with oiled bodies, with the sole purpose of pleasing the powerful man to whom they had given themselves. Much of this is recorded in art from that period, usually portraying groups of attractive women lounging nude by spas and pools.

A centuries-old theme in Western culture is the depiction of European women forcibly taken into Oriental harems – evident for example in the Mozart opera Die Entführung aus dem Serail (“The Abduction from the Seraglio”) concerning the attempt of the hero Belmonte to rescue his beloved Konstanze from the seraglio/harem of the Pasha Selim; or in Voltaire’s Candide, in chapter 12 of which the old woman relates her experiences of being sold into harems across the Ottoman Empire.

Much of Verdi’s opera Il corsaro takes place in the harem of the Pasha Seid – where Gulnara, the Pasha’s favorite, chafes at life in the harem, and longs for freedom and true love. Eventually she falls in love with the dashing invading corsair Corrado, kills the Pasha and escapes with the corsair – only to discover that he loves another woman.

The Lustful Turk, a well-known British erotic novel, was also based on the theme of Western women forced into sexual slavery in the harem of the Dey of Algiers, while in A Night in a Moorish Harem, a Western man is invited into a harem and enjoys forbidden sex with nine concubines. In both works, the theme of “West vs. Orient” is clearly interwoven with the sexual themes.

In popular culture

The same theme was and still is repeated in numerous historical novels and thrillers. For example, Angélique and the Sultan, part of the bestselling French Angélique series by Sergeanne Golon, in which a 17th-century French noblewoman is captured by pirates, sold into the harem of the King of Morocco, stabs the King when he tries to have sex with her and stages a daring escape.

In Leonid Solovyov’s well-known Russian novel Tale of Hodja Nasreddin (translated to English as The Beggar in the Harem: Impudent Adventures in Old Bukhara), a central plot element is the protagonist’s efforts to rescue his beloved from the harem of the Emir of Bukhara – an element not present in the original tales of the Middle Eastern folk hero Nasreddin, on which the novel was loosely based.

H. Beam Piper used the theme in a science fiction context, portraying a gang which kidnaps girls from a Western-dominated, technologically advanced timeline and sells them to a sultan’s harem in an Asian-dominated timeline.

The theme is also present in the Galactic Empire of Poul Anderson’s Dominic Flandry series. The 1954 story “Warriors from Nowhere” includes an episode where “Ella the slave, who had been Ella McIntre and a free woman of Varrak’s hills” is taken into the harem of the evil Duke Alfred of Tauria. The harem depicted fits all conventions of the genre, except that the traditional eunuchs are replaced by reptilian aliens; and like earlier male heroes, the dashing Flandry manages to break into the harem and save Ella in the nick of time.

In the Soviet movie White Sun of the Desert the main character is a Red Army soldier protecting women from an abandoned harem, while also inciting them to live a Soviet lifestyle.

Much of the plot of The Janissary Tree – a 2006 historical crime novel by Jason Goodwin, set in Istanbul in 1836 – takes place in the sultan’s harem, with the main protagonist being the eunuch detective Yashim. The book in many ways aims to overturn the above stereotypes and rooted conventions. For example, in one scene the sultan groans inwardly when a new concubine is brought to his bed, since he does not feel sexual at all and would much rather send her away and curl up with a book. He does not, however, have that option; were he to reject the concubine, “she would spend the whole night crying bitterly, by the morning the whole palace will hear that the Sultan has become impotent, by noon all Istanbul will know it, and within a week the rumour will reach the entire empire.”

Gallery

- Depictions of Harems

Bibliography

- Mohammed Webb. The Influence of Islam on Social Conditions Paper, World Parliament of Religions, Chicago, 1893.

- TheOttomans.org. Historical web site.

- Leslie P. Peirce. The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire, new ed. Oxford University Press USA, 1993. ISBN 0-19-508677-5

- Suraiya Faroqhi. Subjects of the Sultan: Culture and Daily Life in the Ottoman Empire. I. B. Tauris, 2005. ISBN 1-85043-760-2

- Billie Melman. Women’s Orients: English Women and the Middle East, 1718-1918. University of Michigan Press, 1992. ISBN 0-472-10332-6

- Alan Duben, Cem Behar, Richard Smith (Series Editor), Jan De Vries (Series Editor), Paul Johnson (Series Editor), Keith Wrightson (Series Editor). Istanbul Households: Marriage, Family and Fertility, 1880-1940, new ed. Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-521-52303-6

- Emmanuel Todd. The Explanation of Ideology: Family Structures and Social Systems. B. Blackwell, 1985. ISBN 0-631-13724-6

- Senani Ponnamperuma. The Story of Sigiriya, Panique Pty Ltd, 2013 pp 124-127, 179. ISBN 978-0987345110.

- Oleg Grabar. The Formation of Islamic Art, rev. & enlarged ed. Yale University Press, 1987. ISBN 0-300-04046-6

- Reina Lewis. Rethinking Orientalism: Women, Travel, And The Ottoman Harem. Rutgers University Press, 2004 ISBN 0813535433, 9780813535432