In Greek mythology, Helen of Troy (Greek ????? Helén?, pronounced [helén?:]), also known as Helen of Sparta, was the daughter of Zeus and Leda, and was a sister of Castor, Pollux, and Clytemnestra. In Greek myths, she was considered to be the most beautiful woman in the world, a representation of ideal beauty. By marriage she was Queen of Laconia, a province within Homeric Greece, the wife of King Menelaus. Her abduction by Paris, Prince of Troy, brought about the Trojan War.

As with all legendary characters who inhabit the Age of Heroes, the legends ascribe divine ancestry to her: as being the daughter of Zeus, King of the Gods, and being hatched by her mother, Leda, from an egg.

At the time of her marriage, she is said to be still very young, and, as the most beautiful woman in the world, to have had many suitors (or lovers) before marrying Menelaus. Furthermore, the legends are ambiguous as to whether her subsequent involvement with Paris is abduction or seduction. Moreover, it is said that, previously, she has already been abducted by (or had eloped with) Theseus, and bore him a child.

The legends speak of a competition between her suitors, for her hand in marriage, in which Menelaus emerges victorious, and of the Oath sworn by all the unsuccessful suitors (known as the Oath of Tyndareus), which Menelaus subsequently invokes, requiring them to provide military assistance in her rescue; an Oath which accordingly culminates in the Trojan War.

The legends recounting Helen’s fate in Troy are contradictary. The classical poet Homer, amongst others, depicts her as a wistful, even a sorrowful, figure, coming to regret her choice and wishing to be reunited with Menelaus; the depiction is of Helen, lonely and helpless, desperate to find sanctuary while Troy is on fire. On the other hand, there are contradictory accounts of a treacherous Helen, who simulates Bacchic rites and rejoices in the carnage.

Ultimately, Helen’s choice was made for her by fate, as Paris was killed in action. Homer’s account of her ultimate destiny reunites her with Menelaus, though other versions of the legend recount her ascending to Olympus instead.

A cult associated with her developed in Hellenistic Laconia, both at Sparta and elsewhere; at Therapne she shared a shrine with Menelaus. She was also worshipped in Attica, and on Rhodes. Helen and Menelaus were both worshiped as gods, not as heroes.

Of her beauty Christopher Marlowe wrote in 1604, in the play Doctor Faustus, the immortal lines:

- Was this the face that launch’d a thousand ships

- And burnt the topless towers of Ilium … ?

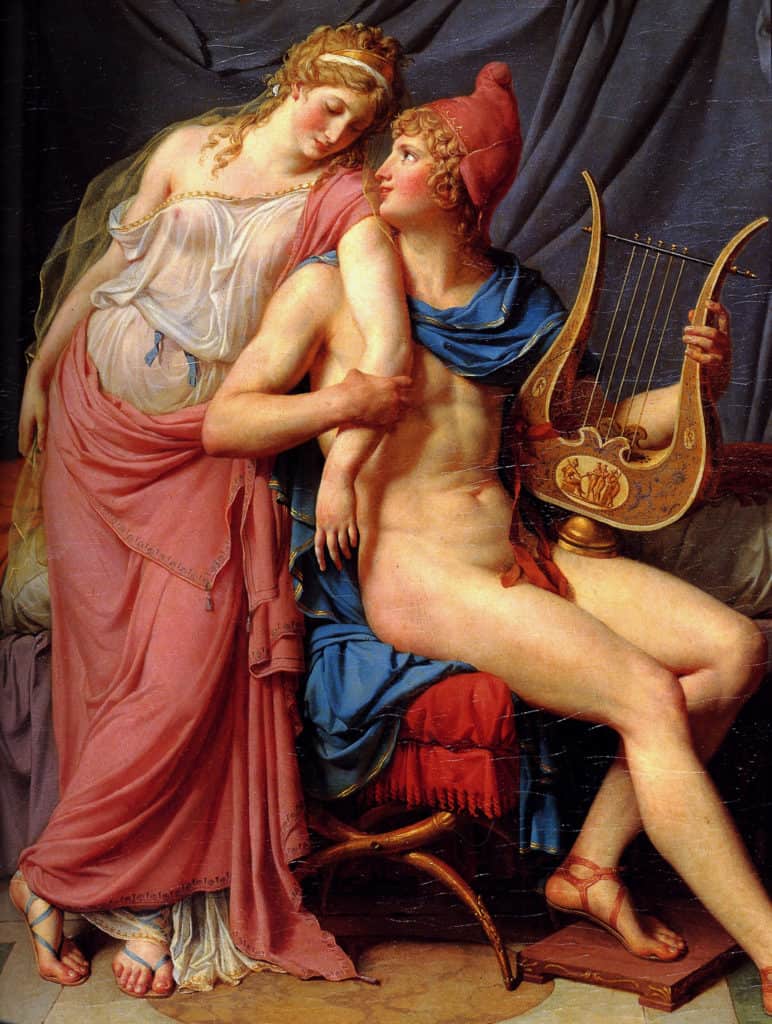

Inspired by the legends of her beauty, Classical, Medieval, Renaissance and modern painting and fine art contains many artistic representations of Helen, who is typically depicted as the personification of ideal beauty.

She starts to be pictured or inscribed in stone, clay and bronze from the 7th Century BC. In classical Greece, her abduction by – or elopment with – Paris was a popular motif. In Medieval illustrations, this event was frequently portrayed as a seduction, whereas in Renaissance painting it is usually depicted as a forcible rape by Paris (for instance, The Rape of Helen by Francesco Primaticcio). And Helen on the ramparts of Troy was a popular theme in late 19th Century art.

Some variants of the legend deny that Helen ever went to Troy. Several classical Greek plays depict her residing in Egypt during the Trojan War, where, although the Trojans tell the Greeks that Helen is not in Troy, the Greeks do not believe them.

The principal literary sources for the legends of the Trojan War and of the Age of Heroes include the writings of the classical authors Aristophanes, Cicero, Euripides and, of course, Homer (including The Iliad and The Odyssey).

Etymology

The etymology of Helen’s name has been and continues to be a problem for scholars. Georg Curtius related Helen (?????) to the moon (Selene ??????). Émile Boisacq considered ????? to derive from the noun ????? meaning “torch”. It has also been suggested that the ? of ????? arose from an original ?, and thus the etymology of the name is connected with the root of Venus. Linda Lee Clader, however, says that none of the above suggestions offers much satisfaction.

None of the etymological sources appear to support the existence, save as a coincidence only, of a connection between the name of Helen and the name by which the classical Greeks commonly described themselves, namely Hellenic or Hellenistic.

Prehistoric and mythological context

The origins of Helen’s myth date back to the Mycenaean age. The first record of her name appears in the poems of Homer, but scholars assume that such myths invented or received by the Mycenaean Greeks made their way to Homer. Her mythological birthplace was Sparta of the Age of Heroes, which features prominently in the canon of Greek myth: in later ancient Greek memory, the Mycenaean Bronze Age became the age of the Greek heroes. The kings, queens, and heroes of the Trojan Cycle are often related to the gods, since divine origins gave stature to the Greeks’ heroic ancestors. The fall of Troy came to represent a fall from an illustrious heroic age, remembered for centuries in oral tradition before being written down. Recent archaeological excavations in Greece suggest that modern-day Laconia was a distinct territory in the Late Bronze Age, while the poets narrate that it was a rich kingdom. Archaeologists have unsuccessfully looked for a Mycenaean palatial complex buried beneath present-day Sparta. An important Mycenaean site at the Menelaion was destroyed by c. 1200 BC, and most other Mycenaean sites in Lakonia also disappear. There is a shrinkage from fifty sites to fifteen in the early twelfth century, and then to fewer in the eleventh century.

Birth

In most sources, including the Iliad and the Odyssey, Helen is the daughter of Zeus and Leda, and the wife of the Spartan king Menelaus. Euripides’ play Helen, written in the late 5th century BC, is the earliest source to report the most familiar account of Helen’s birth: that, although her putative father was Tyndareus, she was actually Zeus’ daughter. In the form of a swan, the king of gods was chased by an eagle, and sought refuge with Leda. The swan gained her affection, and the two mated. Leda then produced an egg, from which Helen emerged. The First Vatican Mythographer introduces the notion that two eggs came from the union: one containing Castor and Pollux; one with Helen and Clytemnestra. Nevertheless, the same author earlier states that Helen, Castor and Pollux were produced from a single egg. Pseudo-Apollodorus states that Leda had intercourse with both Zeus and Tyndareus the night she conceived Helen.

On the other hand, in the Cypria, one of the Cyclic Epics, Helen was the daughter of Zeus and the goddess Nemesis. The date of the Cypria is uncertain, but it is generally thought to preserve traditions that date back to at least the 7th century BC. In the Cypria, Nemesis did not wish to mate with Zeus. She therefore changed shape into various animals as she attempted to flee Zeus, finally becoming a goose. Zeus also transformed himself into a goose and mated with Nemesis, who produced an egg from which Helen was born. Presumably, in the Cypria, this egg was somehow transferred to Leda. Later sources state either that it was brought to Leda by a shepherd who discovered it in a grove in Attica, or that it was dropped into her lap by Hermes.

Asclepiades of Tragilos and Pseudo-Eratosthenes related a similar story, except that Zeus and Nemesis became swans instead of geese. Timothy Gantz has suggested that the tradition that Zeus came to Leda in the form of a swan derives from the version in which Zeus and Nemesis transformed into birds.

Pausanias states that in the middle of the 2nd century AD, the remains of an egg-shell, tied up in ribbons, were still suspended from the roof of a temple on the Spartan acropolis. People believed that this was “the famous egg that legend says Leda brought forth”. Pausanias traveled to Sparta to visit the sanctuary, dedicated to Hilaeira and Phoebe, in order to see the relic for himself.

Abduction by Theseus and youth

Two Athenians, Theseus and Pirithous, thought that since they were both sons of gods, both of them should have divine wives; they thus pledged to help each other abduct two daughters of Zeus. Theseus chose Helen, and Pirithous vowed to marry Persephone, the wife of Hades. Theseus took Helen and left her with his mother Aethra or his associate Aphidnus at Aphidnae or Athens. Theseus and Pirithous then traveled to the underworld, the domain of Hades, to kidnap Persephone. Hades pretended to offer them hospitality and set a feast, but, as soon as the pair sat down, snakes coiled around their feet and held them there. Helen’s abduction caused an invasion of Athens by Castor and Pollux, who captured Aethra in revenge, and returned their sister to Sparta.

In most accounts of this event, Helen was quite young; Hellanicus of Lesbos said she was seven years old and Diodorus makes her ten years old. On the other hand, Stesichorus said that Iphigeneia was the daughter of Theseus and Helen, which obviously implies that Helen was of childbearing age. In most sources, Iphigeneia is the daughter of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra, but Duris of Samos and other writers followed Stesichorus’ account.

Ovid’s Heroides give us an idea of how ancient and, in particular, Roman authors imagined Helen in her youth: she is presented as a young princess wrestling naked in the palaestra; an image alluding to a part of girls’ physical education in classical (and not in Mycenaean) Sparta. Sextus Propertius imagines Helen as a girl who practices arms and hunts with her brothers:

[…] or like Helen, on the sands of Eurotas, between Castor and Pollux, one to be victor in boxing, the other with horses: with naked breasts she carried weapons, they say, and did not blush with her divine brothers there.

Suitors of Helen

When it was time for Helen to marry, many kings and princes from around the world came to seek her hand, bringing rich gifts with them, or sent emissaries to do so on their behalf. During the contest, Castor and Pollux had a prominent role in dealing with the suitors, although the final decision was in the hands of Tyndareus. Menelaus, her future husband, did not attend but sent his brother, Agamemnon, to represent him.

There are three available and not entirely consistent lists of suitors, compiled by Pseudo-Apollodorus (31 suitors), Hesiod (11 suitors), and Hyginus (36 suitors), for a total of 45 distinct names. There are only fragments from Hesiod’s poem, so his list would have contained more. Achilles’ absence from the lists is conspicuous, but Hesiod explains that he was too young to take part in the contest. Taken together, the list of suitors matches well with the captains in the Catalog of Ships from the Iliad; however, some of the names may have been placed in the list of Helen’s suitors simply because they went to Troy. It is not unlikely that relatives of a suitor may have joined the war.

Six Suitors listed in all three sources

- Ajax – Son of Telamon. Led 12 ships from Salamis to Troy. Commits suicide there.

- Elephenor – Son of Chalcodon. Led 50 ships to Troy and died there

- Menelaus – Son of Atreus. Led 60 ships from Sparta to Troy. He returned home to Sparta with Helen.

- Menestheus – Son of Peteos. Led 50 ships from Athens to Troy. He returned to Athens after the war.

- Odysseus – Son of Laertes. Led 12 ships from Ithaca to Troy. He returned home after 10 years of wandering the seas.

- Protesilaus – Son of Iphicles. Led 40 ships from Phylace to Troy. He was the first Greek to die in battle at the hands of Hector.

Nineteen Suitors listed by both Apollodorus and Hyginus

- Agapenor – Son of Ancaeus, King of Arcadia. Takes 60 ships of men to Troy. Returns home.

- Ajax (AKA Ajax the Lesser or Locrian Ajax) – Son of Oileus. Led 40 ships to Troy, drowned on the way home when Poseidon split the rock he was on.

- Amphimachus – Son of Cteatus. With Polyxenus and Thalpius, he led 40 ships from Elis to Troy. Killed by Hector.

- Antilochus – Son of Nestor. Went with his father and 90 ships to Troy. Killed in battle while protecting his father from Memnon.

- Ascalaphus – Son of Ares and King of Orchemenus. Led 30 ships to Troy. Killed in battle by Deiphobus.

- Diomedes – Son of Tydeus. Diomedes was one of the Epigoni and King of Argos. He led 80 ships to Troy. His wife took a lover and Diomedes lost his kingdom, so after the war he settled in Italy.

- Eumelus – Son of Admetus and King of Pherae. Led 11 ships to Troy.

- Eurypylus – Son of Euaemon. Led 40 ships from Thessaly to Troy.

- Leonteus – Son of Coronos. With Polypoetes he led 40 ships of the Lapiths to Troy.

- Machaon – Son of Asclepius, brother of Podalirius. An Argonaut and physician. Led 30 ships. Killed in battle by Eurypylus (the son of Telephus).

- Meges – Son of Phyleus. Led 40 ships to Troy.

- Patroclus – Son of Menoetius. His younger cousin Achilles went with him to Troy. Killed by Hector.

- Peneleos – Son of Hippalcimus. An Argonaut. He went with the Boetian force of 50 ships to Troy. Killed in battle by Eurypylus (the son of Telephus).

- Philoctetes – Son of Poeas. Led 7 ships from Thessaly to Troy, he was an archer and killed Paris.

- Podalirius – Son of Asclepius, brother of Machaon. A physician. After the war he founded a city in Caria.

- Polypoetes – Son of Pirithous. With Leonteus, he led 40 ships of the Lapiths to Troy.

- Polyxenus – Son of Agasthenes. With Amphimachus, and Thalpius, he led 40 ships from Elis to Troy.

- Sthenelus – Son of Capaneus. One of the Epigoni, he went with Diomedes to Troy.

- Thalpius – Son of Eurytus. With Amphimachus and Polyxenus, he led 40 ships from Elis to Troy.

One Suitor listed by Apollodorus and Hesiod

- Amphilochus – Son of Amphiaraus and younger brother of Alcmaeon.

One Suitor listed by Hesiod and Hyginus

- Idomeneus – Son of Deucalion and King of Crete. Led 80 ships to Troy. Survived the war, but was exiled from Crete.

Three Suitors listed only by Hesiod

- Alcmaeon – Son of Amphiaraus and one of the Epigoni.

- Lycomedes – a Cretan.

- Podarces – The younger brother of Protesilaus. He led the troops after his brother’s death.

Ten Suitors listed only by Hyginus

- Ancaeus –

- Blanirus –

- Clytius –

- Meriones – A companion of Idomeneus of Crete.

- Nireus – He led 3 ships from Syme to Troy.

- Phemius –

- Phidippus – He led 30 ships to Troy.

- Prothous – He led 40 ships from Magnetes to Troy.

- Thoas – He led 40 ships from Aetolia to Troy.

- Tlepolemus – He led 9 ships from Rhodes to Troy.

Five Suitors listed only by Apollodorus

- Epistrophus – Son of Iphitus, brother of Schedius.

- Ialmenus – Companion of Ascalaphus, who led 30 ships to Troy

- Leitus – Son of Alector

- Schedius – Son of Iphitus, brother of Epistrophus. He was killed by Hector who was trying to throw a spear towards Ajax.

- Teucer – The half-brother of Ajax. Survived the war.

The Oath of Tyndareus

Tyndareus was afraid to select a husband for his daughter, or send any of the suitors away, for fear of offending them and giving grounds for a quarrel. Odysseus was one of the suitors, but had brought no gifts because he believed he had little chance to win the contest. He thus promised to solve the problem, if Tyndareus in turn would support him in his courting of Penelope, the daughter of Icarius. Tyndareus readily agreed, and Odysseus proposed that, before the decision was made, all the suitors should swear a most solemn oath to defend the chosen husband against whoever should quarrel with him. After the suitors had sworn not to retaliate, Menelaus was chosen to be Helen’s husband. As a sign of the importance of the pact, Tyndareus sacrificed a horse. Helen and Menelaus became rulers of Sparta, after Tyndareus and Leda abdicated. Menelaus and Helen rule in Sparta for at least ten years; they have a daughter, Hermione, and (according to some myths) three sons: Aethiolas, Maraphius, and Pleisthenes.

The marriage of Helen and Menelaus marks the beginning of the end of the age of heroes. Concluding the catalog of Helen’s suitors, Hesiod reports Zeus’ plan to obliterate the race of men and the heroes in particular. The Trojan War, caused by Helen’s elopement with Paris, is going to be his means to this end.

Seduction by Paris

Paris, a Trojan prince, came to Sparta to claim Helen, in the guise of a supposed diplomatic mission. Before this journey, Paris had been appointed by Zeus to judge the most beautiful goddess; Hera, Athena, or Aphrodite. In order to earn his favour, Aphrodite promised Paris the most beautiful woman in the world. Swayed by Aphrodite’s offer, Paris chose her as the most beautiful of the goddesses, earning the wrath of Athena and Hera.

Although Helen is sometimes depicted as being raped by Paris, Ancient Greek sources are often elliptical and contradictory. Herodotus states that Helen was abducted, but the Cypria simply mentions that, after giving Helen gifts, “Aphrodite brings the Spartan queen together with the Prince of Troy.” Sappho argues that Helen willingly left behind Menelaus and their nine-year-old daughter, Hermione, to be with Paris:

- Some say a host of horsemen, others of infantry and others

- of ships, is the most beautiful thing on the dark earth

- but I say, it is what you love

- Full easy it is to make this understood of one and all: for

- she that far surpassed all mortals in beauty, Helen her

- most noble husband

- Deserted, and went sailing to Troy, with never a thought for

- her daughter and dear parents.

Dio Chrysostom gives a completely different account of the story, questioning Homer’s credibility: after Agamemnon had married Helen’s sister, Klytaemnestra, Tyndareus sought Helen’s hand for Menelaus on account of political reasons. However, Helen was sought by many suitors, who came from far and near, among them Paris who surpassed all the others and won the favor of Tyndareus and his sons. Thus he won her fairly and took her away to Troia, with the full consent of her natural protectors. Cypria narrate that in just three days Paris and Helen reached Troy. Homer narrates that during a brief stop-over in the small island of Kranai, according to Iliad, the two lovers consummated their passion. On the other hand, Cypria note that this happened the night before they left Sparta.

Helen in Egypt

At least three Ancient Greek authors denied that Helen ever went to Troy; instead, they suggested, Helen stayed in Egypt during the duration of the Trojan War. Those three authors are Euripides, Stesichorus, and Herodotus. In the version put forth by Euripides in his play Helen, Hera fashioned a likeness of Helen (eidolon, ???????) out of clouds at Zeus’ request, Hermes took her to Egypt, and Helen never went to Troy, spending the entire war in Egypt. Eidolon is also present in Stesichorus’ account, but not in Herodotus’ rationalizing version of the myth.

Herodotus adds weight to the “Egyptian” version of events by putting forward his own evidence–he traveled to Egypt and interviewed the priests of the temple of (Foreign Aphrodite, ?????? ?????????) at Memphis. According to these priests, Helen had arrived in Egypt shortly after leaving Sparta, because strong winds had blown Paris’s ship off course. King Proteus of Egypt, appalled that Paris had seduced his host’s wife and plundered his host’s home in Sparta, disallowed Paris from taking Helen to Troy. Paris returned to Troy without a new bride, but the Greeks refused to believe that Helen was in Egypt and not within Troy’s walls. Thus, Helen waited in Memphis for ten years, while the Greeks and the Trojans fought. Following the conclusion of the Trojan War, Menelaus sailed to Memphis, where Proteus reunited him with Helen.

Helen in Troy

When he discovered that his wife was missing, Menelaus called upon all the other suitors to fulfill their oaths, thus beginning the Trojan War. The Greek fleet gathered in Aulis, but the ships could not sail, because there was no wind. Artemis was enraged with a sacrilegious act of the Greeks, and only the sacrifice of Agamemnon’s daughter, Iphigenia, could appease her. In Euripides Iphigenia in Aulis, Clytemnestra, Iphigenia’s mother and Helen’s sister, begs her husband to reconsider his decision, calling Helen a “wicked woman”. Clytemnestra (unsuccessfully) warns Agamemnon that sacrificing Iphigenia for Helen’s sake is, “buying what we most detest with what we hold most dear”.

Before the opening of hostilities, the Greeks dispatched a delegation to the Trojans under Odysseus and Menelaus; they endeavored to persuade Priam to hand Helen back without success. A popular theme, The Request of Helen (Helenes Apaitesis, ?????? ?????????), was the subject of a drama by Sophocles, now lost.

Homer paints a poignant, lonely picture of Helen in Troy. She is filled with self-distaste and regret for what she has caused; by the end of the war, the Trojans have come to hate her. When Hector dies, she is the third mourner at his funeral, and she says that, of all the Trojans, Hector and Priam alone were always kind to her:

- Wherefore I wail alike for thee and for my hapless self with grief at heart;

- for no longer have I anyone beside in broad Troy that is gentle to me or kind;

- but all men shudder at me.

These bitter words reveal that Helen gradually realized Paris’ weaknesses, and she decided to ally herself with Hector. There is an affectionate relationship between the two of them, and Helen has harsh words to say for Paris, when she compares the two brothers:

- Howbeit, seeing the gods thus ordained these ills, would that I had been wife to a better man,

- that could feel the indignation of his fellows and their many revilings. […]

- But come now, enter in, and sit thee upon this chair, my brother,

- since above all others has trouble encompassed thy heart because of shameless me, and the folly of Alexander.

After Paris was killed in action, there was some dispute among the Trojans about which of Priam’s surviving sons she should remarry: Helenus or Deiphobus, but she was given to the latter.

During the fall of Troy, Helen’s role is ambiguous. In Virgil’s Aeneid, Deiphobus gives an account of Helen’s treacherous stance: when the Trojan Horse was admitted into the city, she feigned Bacchic rites, leading a chorus of Trojan women, and, holding a torch among them, she signaled to the Greeks from the city’s central tower. In Odyssey, however, Homer narrates a different story: Helen circled the Horse three times, and she imitated the voices of the Greek women left behind at home–she thus tortured the men inside (including Odysseus and Menelaus) with the memory of their loved ones, and brought them to the brink of destruction.

After the death of Hector and Paris, Helen became the paramour of their younger brother, Deiphobus; but when the sack of Troy began, she hid her new husband’s sword, and left him to the mercy of Menelaus and Odysseus. In Aeneid, Aeneas meets the mutilated Deiphobus in Hades; his wounds serve as a testimony to his ignominious end, abetted by Helen’s final act of treachery.

However, Helen’s portraits in Troy seem to contradict each other. From one side, we read about the treacherous Helen who simulated Bacchic rites and rejoiced over the carnage of Trojans. On the other hand, there is another Helen, lonely and helpless; desperate to find sanctuary, while Troy is on fire. Stesichorus narrates that both Greeks and Trojans gathered to stone her to death. When Menelaus finally found her, he raised his sword to kill her. He had demanded that only he should slay his unfaithful wife; but, when he was ready to do so, she dropped her robe from her shoulders, and the sight of her beauty caused him to let the sword drop from his hand. Electra wails:

Alas for my troubles! Can it be that her beauty has blunted their swords?

Fate

Helen returned to Sparta and lived for a time with Menelaus, where she was encountered by Telemachus in The Odyssey. According to another version, used by Euripides in his play Orestes, Helen had long ago left the mortal world by then, having been taken up to Olympus almost immediately after Menelaus’ return.

According to Pausanias the geographer (3.19.9-10): “The account of the Rhodians is different. They say that when Menelaus was dead, and Orestes still a wanderer, Helen was driven out by Nicostratus and Megapenthes and came to Rhodes, where she had a friend in Polyxo, the wife of Tlepolemus. For Polyxo, they say, was an Argive by descent, and when she was already married to Tlepolemus, shared his flight to Rhodes. At the time she was queen of the island, having been left with an orphan boy. They say that this Polyxo desired to avenge the death of Tlepolemus on Helen, now that she had her in her power. So she sent against her when she was bathing handmaidens dressed up as Furies, who seized Helen and hanged her on a tree, and for this reason the Rhodians have a sanctuary of Helen of the Tree.”

Tlepolemus was a son of Heracles and Astyoche. Astyoche was a daughter of Phylas, King of Ephyra who was killed by Heracles. Tlepolemus was killed by Sarpedon on the first day of fighting in the Iliad. Nicostratus was a son of Menelaus by his concubine Pieris, an Aetolian slave. Megapenthes was a son of Menelaus by his concubine Tereis, no further origin.

In Simonianism, it was taught that Helen of Troy was one of the incarnations of the Ennoia in human form.

Artistic representations

From Antiquity, depicting Helen would be a remarkable challenge. The story of Zeuxis deals with this exact question: how would an artist immortalize ideal beauty? He eventually selected the best features from five virgins. The ancient world starts to paint Helen’s picture or inscribe her form on stone, clay and bronze by the 7th century BC. Helen is frequently depicted on Athenian vases as being threatened by Menelaus and fleeing from him. This is not the case, however, in Laconic art: on an Archaic stele depicting Helen’s recovery after the fall of Troy, Menelaus is armed with a sword but Helen faces him boldly, looking directly into his eyes; and in other works of Peloponnesian art, Helen is shown carrying a wreath, while Menelaus holds his sword aloft vertically. In contrast, on Athenian vases of c. 550-470, Menelaus threateningly points his sword at her.

The abduction by Paris was another popular motif in ancient Greek vase-painting; definitely more popular than the kidnapping by Theseus. In a famous representation by the Athenian vase painter Makron, Helen follows Paris like a bride following a bridegroom, her wrist grasped by Paris’ hand. The Etruscans, who had a sophisticated knowledge of Greek mythology, demonstrated a particular interest in the theme of the delivery of Helen’s egg, which is depicted in relief mirrors.

In Renaissance painting, Helen’s departure from Sparta is usually depicted as a scene of forcible removal (rape) by Paris. This is not, however, the case with certain secular medieval illustrations. Artists of the 1460s and 1470s were influenced by Guido delle Colonne’s Historia destructionis Troiae, where Helen’s abduction was portrayed as a scene of seduction. In the Florentine Picture Chronicle Paris and Helen are shown departing arm in arm, while their marriage was depicted into Franco-Flemish tapestry.

In Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus (1604), Faust conjures the shade of Helen. Upon seeing Helen, Faustus speaks the famous line: “Was this the face that launch’d a thousand ships, / And burnt the topless towers of Ilium.” (Act V, Scene I.) Helen is also conjured by Faust in Goethe’s Faust.

In Pre-Raphaelite art, Helen is often shown with shining curly hair and ringlets. Other painters of the same period depict Helen on the ramparts of Troy, and focus on her expression: her face is expressionless, blank, inscrutable. In Gustave Moreau’s painting, Helen will finally become faceless; a blank eidolon in the middle of Troy’s ruins.

Cult

The major centers of Helen’s cult were in Laconia. At Sparta, the urban sanctuary of Helen was located near the Platanistas, so called for the plane trees planted there. Ancient sources associate Helen with gymnastic exercises or/and choral dances of maidens near the Evrotas River. Theocritus conjures the song epithalamium Spartan women sung at Platanistas commemorating the marriage of Helen and Menelaus:

- We first a crown of low-growing lotus

- having woven will place it on a shady plane-tree.

- First from a silver oil-flask soft oil

- drawing we will let it drip beneath the shady plane-tree.

- Letters will be carved in the bark, so that someone passing by

- may read in Doric: “Reverence me. I am Helen’s tree.”

Helen’s worship was also present on the opposite bank of Eurotas at Therapne, where she shared a shrine with Menelaus and the Dioscuri. The shrine has been known as “Menelaion” (the shrine of Menelaus), and it was believed to be the spot where Helen was buried alongside Menelaus. Despite its name, both the shrine and the cult originally belonged to Helen; Menelaus was added later as her husband. Isocrates writes that at Therapne Helen and Menelaus were worshiped as gods, and not as heroes. Clader argues that, if indeed Helen was worshiped as a goddess at Therapne, then her powers should be largely concerned with fertility. There is also evidence for Helen’s cult in Hellenistic Sparta: rules for those sacrificing and holding feasts in their honor are extant.

Helen was also worshiped in Attica along with her brothers, and on Rhodes as Helen Dendritis (Helen of the Trees, ????? ?????????); she was a vegetation or a fertility goddess. Martin F. Nilsson has argued that the cult in Rhodes has its roots to the Minoan, pre-Greek era, when Helen was allegedly worshiped as a vegetation goddess. Claude Calame and other scholars try to analyze the affinity between the cults of Helen and Artemis Orthia, pointing out the resemblance of the terracotta female figurines offered to both deities.

In modern culture

- Helen appears in various versions of the Faust myth, such as Marlowe’s 1604 play The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus, in which Faustus’s summoning of Helen and courting her is one of the best-known scenes, and which contributed the line “Was this the face that launched a thousand ships…?” which inspired many later references to Helen (see below).

- German poet and polymath Johann Wolfgang von Goethe re-envisioned the meeting of Faust and Helen. In Faust: The Second Part of the Tragedy, the union of Helen and Faust becomes a complex allegory of the meeting of the classical-ideal and modern worlds.

- Rupert Brooke’s poem Menelaus and Helen portrays an aging Helen who has born “Child on legitimate child” and become a shrill voiced scold who weeps at memories of the dead Paris.

- Irish poet William Butler Yeats compared Helen to his lover, Maude Gonne, in his 1916 poem “No Second Troy”.

- In 1927, the film Metropolis by Fritz Lange has the unseen character of Hel, who was the deceased wife of Joh Fredersen and the object of desire of Dr. Rotwang, which inspired him to create the automaton. This quest for the woman ultimately led to the downfall of Fredersen’s empire. There are also multiple references comparing the Metropolis to the Tower of Babel in Egypt, where Helen of Troy was said to have resided during the Trojan War.

- In 1928, Richard Strauss wrote the German opera Die ägyptische Helena, The Egyptian Helena, which is the story of Helen and Menelaus’s troubles when they are marooned on a mythical island.

- In 1928, a silent film The Private Life of Helen of Troy, was made.

- The 1951 Swedish film Sköna Helena is an adapted version of Offenbach’s operetta, starring Max Hansen and Eva Dahlbeck

- Henry Rider Haggard wrote a novel, The World’s Desire in which Odysseus finds Helen in Egypt as a priestess and they wed.

- The anthology The Dark Tower by C. S. Lewis includes a fragment entitled “After Ten Years”. In Egypt after the Trojan War, Menelaus is allowed to choose between the real, disappointing Helen and an ideal Helen conjured by Egyptian magicians. Which would Menelaus choose?

- In 1956, a Franco-British epic titled Helen of Troy was released, directed by Oscar-winning director Robert Wise and starring Italian actress Rossana Podestà in the title role. It was filmed in Italy, and featured well-known British character actors such as Harry Andrews, Cedric Hardwicke, and Torin Thatcher in supporting roles.

- In 1965, a 4-part Doctor Who television serial known as The Myth Makers, written by Donald Cotton, placed the eponymous time traveller in Troy during the siege of the city by the Greeks, and depicted the Fall of Troy. In this humourous portrayal, the Heroes of Antiquity were all depicted as cowards, and Helen as a serial adulterer who repeatedly ran away to the ends of the Earth with other men, in despite of her long-suffering husband, who heartily wished he could abandon the ten year siege without becoming a laughing-stock.

- A 1966 episode of The Time Tunnel titled “Revenge of the Gods” placed the time travelers at the sacking of Troy. Dee Hartford portrayed Helen.

- In 1968, Star Trek: The Original Series produced an episode entitled “Elaan of Troyius”, a corruption of ‘Helen of Troy’, in which a woman’s beauty causes problems for the crew of the Enterprise.

- In 1971, Michael Cacoyannis directed a film version of The Trojan Women in which Helen is played by Irene Papas.

- John Cale’s 1975 album Helen of Troy and its title track are named after her.

- In 1996, Helen appeared in the twelfth episode of Season 1 of the TV series Xena: Warrior Princess called “Beware Greeks Bearing Gifts”. Played by Galyn Görg, Helen was supposedly a close friend of Xena’s and sent out a messenger to fetch her during the Trojan War. This incarnation of Helen did once love Paris, but is now worried that he has become obsessed with keeping her. She also does not truly wish to return to Menelaus, but rather wants to live independently.

- Helen of Troy is referenced in Episode 11 of Season 5 called “Comes A Horseman” in Highlander: The Series.

- A 2003 television version of Helen’s life up to the fall of Troy, Helen of Troy, in which she was played by Sienna Guillory.

- Helen was portrayed by Diane Kruger in the 2004 film Troy. In this adaptation she does not return to Sparta with Menelaus but leaves Troy with Paris when the city falls.

- Margaret George wrote an epic adult novel, Helen of Troy, in 2006, told through Helen’s first-person narrative.

- Esther Friesner wrote a young-adult novel, Nobody’s Princess, published in 2007, of Helen’s childhood and early life, and its sequel, Nobody’s Prize.

- In 2008 BBC Radio 4 broadcast a trilogy of plays under the umbrella title of Troy: “Priam and His Sons”, “The Death of Achilles” and “Helen in Ephesus” written by Andrew Rissik and featuring Geraldine Somerville as Helen. Helen is depicted as originally being self-absorbed and concerned only with her own desires and fleeing with Paris to Troy by her own choice; after Troy falls, she is forgiven and taken back by Menelaus, but on the way back to Sparta their ship is wrecked in a storm. Helen is rescued by pirates who rape her and permanently scar her face. She is sold as a slave in Ephesus and bought by a weaver and healer named Parmenion, with whom she lives chastely for two years and learns inner peace before she returns to Sparta to be reunited with Menelaus and restore his tortured soul.

- Jacob M. Appel’s 2008 play, Helen of Sparta, retells Homer’s Iliad from Helen’s point of view.

- The band Glass Wave entitled a song on their 2010 album “Helen”. In the song, Helen remembers her life before the Trojan War.

- Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark’s 2013 album English Electric features a track entitled “Helen of Troy”.

- In 2014, The Princess of Sparta: Heroes of the Trojan War, the first book of ten by Aria Cunningham, tells the epic love story of Helen and Paris, setting the mythology into the historical context of the Late Bronze Age.

- Inspired by the line, “Was this the face that launched a thousand ships…?” from Marlowe’s Faustus, Isaac Asimov jocularly coined the unit “millihelen” to mean the amount of beauty that can launch one ship.

- In the book Pretties, second in the Uglies series by Scott Westerfeld, the character of Zane often rates the beauty or excitement of things in “milli-helens” (see the definition by Isaac Asimov, above).

- Helen of Troy is referenced in the climactic scene of The Truth About Cats & Dogs.

- Caroline B. Cooney also wrote a young-adult novel, Goddess of Yesterday, where Helen is one of the main characters.

- Josephine Angelini wrote a young adult novel, Starcrossed about Helen of Troy.

- Canadian novelist and poet Margaret Atwood re-envisioned the myth of Helen in modern, feminist guise in her poem “Helen of Troy Does Countertop Dancing”.

- Frederick Rolfe, in The Weird of the Wanderer, has the hero (Nicholas Crabbe) discover that he is a reincarnation of Odysseus and marry Helen: both are deified.

- Also inspired by the same Marlowe quotation is “If a face could launch a thousand ships, then where am I to go?”, a line from the song “If” by David Gates and Bread.

- The modernist poet H.D. wrote an epic poem Helen in Egypt from Helen’s perspective.

- The Memoirs of Helen of Troy by Amanda Elyot is about the life of Helen.

- In the movie English dubbed version of Kung Fu Hustle, The Beast asks if they are the fated Lovers, to which the Landlord and Landlady refer to themselves as Paris and Helen of Troy.

- Her cuff bracelet is briefly mentioned in a Warehouse 13 episode as having seductive properties.

- In the novel Faust Among Equals by Tom Holt, the relationship between Faust and Helen of Troy is a central theme.

- Kimberly-Clark’s TV campaign for Poise adult underwear with Whoopi Goldberg as Helen.

- Helen of Troy appears as a recurring character in Disney’s Hercules: The Animated Series as the most popular student of Prometheus Academy and girlfriend of Adonis.

- Olivia Pope in ABC’s hit show Scandal was referred to as Helen of Troy “the face that launched a thousand ships”.

Primary sources

- Aristophanes, Lysistrata. For an English translation see the Perseus Project.

- Cicero, De inventione II.1.1-2

- Cypria, fragments 1, 9, and 10. For an English translation see the Online Medieval and Classical Library.

- Dio Chrysostom, Discourses. For an English translation, see Lacus Curtius.

- Euripides, Helen. For an English translation, see the Perseus Project.

- Euripides, Iphigenia in Aulis. For an English translation, see the Perseus project.

- Euripides, Orestes. For an English translation, see the Perseus Project.

- Herodotus, Histories, Book II. For an English translation, see the Perseus Project.

- Hesiod, Catalogs of Women and Eoiae. For an English translation see the Online Medieval and Classical Library.

- Homer, Iliad, Book III; Odyssey, Books IV, and XXIII.

- Hyginus, Fables. Translated in English by Mary Grant.

- Isocrates, Helen. For an English translation, see the Perseus Project.

- Servius, In Aeneida I.526, XI.262

- Lactantius Placidus, Commentarii in Statii Thebaida I.21.

- Little Iliad, fragment 13. For an English translation, see the Online Medieval and Classical Library.

- Ovid, Heroides, XVI.Paris Helenae. For an English translation, see the Perseus Project.

- Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book III. For an English translation, see the Perseus Project.

- Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca, Book III; Epitome.

- Sappho, fragment 16.

- Sextus Propertius, Elegies, 3.14. Translated in English by A.S. Kline.

- Theocritus, Idylls, XVIII (The Epithalamium of Helen). Translated in English by J. M. Edmonds.

- Virgil, Aeneid. Book VI. For an English translation see the Perseus Project.

Secondary sources

- Allan, Williams (2008). “Introduction”. Helen. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-83690-5.

- Anderson, Michael John (1997). “Further Directions”. The Fall of Troy in early Greek Poetry and Art. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-815064-4.

- Cairns, Francis (2006). “A Lighter Shade of Praise”. Sextus Propertius. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-86457-7.

- Calame, Claude (2001). “Chorus and Ritual”. Choruses of Young Women in Ancient Greece (translated by Derek Collins and Janice Orion). Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-7425-1525-7.

- Caprino, Alexandra (1996). “Greek Mythology in Etruria”. In Franklin Hall; John. Etruscan Italy. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-8425-2334-0.

- Chantraine, Pierre (2000). “?????”. Dictionnaire Étymologique de la Langue Gercque (in French). Klincksieck. ISBN 2-252-03277-4.

- Cingano, Ettore (2005). “A Catalog within a Catalog: Helen’s Suitors in the Hesiodic Catalog of Women”. In Hunter; Richard L. The Hesiodic Catalog of Women. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-83684-0.

- Clader, Linda Lee (1976). Helen. Brill Archive. ISBN 90-04-04721-2.

- Cyrino, Monica S. (2006). “Helen of Troy”. In Winkler; Martin M. Troy: from Homer’s Iliad to Hollywood. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 1-4051-3182-9.

- David, Benjamin (2005). “Narrative in Context”. In Jenkens, Lawrence A. Renaissance Siena. Truman State University. ISBN 1-931112-43-6.

- Eaverly, Mary Ann (1995). “Geographical and Chronological Distribution”. Archaic Greek Equestrian Sculpture. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-10351-2.

- Edmunds, Lowell (May 2007). “Helen’s Divine Origins”. Electronic Antiquity: Communicating the Classics X (2): 1-44. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- Frisk, Hjalmar (1960). “?????”. Griechisches Etymologisches Wörterbuch (in German) I. French & European Pubns.

- Gantz, Timothy (2004). Early Greek Myth. Baltimore, MD and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-5362-1.

- Gumpert, Matthew (2001). “Helen in Greece”. Grafting Helen. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0-299-17124-8.

- Hard, Robin; Rose, Herbert Jennings (2004). “the Trojan War”. The Routledge Handbook of Greek Mythology. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-18636-6.

- Hughes, Bettany (2005). Helen of Troy: Goddess, Princess, Whore. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-224-07177-7.

- Executive ed.: Joseph P. Pickert… (2000). “Indo-European roots: wel?“. The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 0-395-82517-2.

- Jackson, Peter (2006). “Shapeshifting Rape and Xoros”. The Transformations of Helen. J.H.Röll Verlag.

- Kim, Lawrence (2010). “Homer, poet and historian”. Homer Between History and Fiction in Imperial Greek Literature. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-19449-5.

- Lindsay, Jack (1974). “Helen in the Fifth Century”. Helen of Troy: Woman and Goddess. Rowman and Littlefield. ISBN 0-87471-581-4.

- Lynn Badin, Stephanie (2006). “Religion and Ideology”. The Ancient Greeks. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-57607-814-0.

- Maguire, Laurie (2009). “Beauty”. Helen of Troy. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 9781405126359.

- Mansfield, Elizabeth (2007). “Helen’s Uncanny Beauty”. Too Beautiful to Picture. University of MinnesotaPress. ISBN 0-8166-4749-6.

- Matheson, Susan B. (1996). “Heroes”. Polygnotos and Vase Painting in Classical Athens. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0-299-13870-4.

- Meagher, Robert E. (2002). The Meaning of Helen. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers. ISBN 0865165106.

- Mills, Sophie (1997). “Theseus and Helen”. Theseus, Tragedy, and the Athenian Empire. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-815063-6.

- Moser, Thomas C. (2004). A Cosmos of Desire. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-11379-8.

- Nilsson, Martin Persson (1932). “Mycenaean Centers and Mythological Centers”. The Mycenaean Origin of Greek Mythology. Forgotten Books. ISBN 1-60506-393-2.

- Pomeroy, Sarah B. (2002). “Education”. Spartan Women. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-513067-7.

- Redfield, James (1994). “The Hero”. The Tragedy of Hector. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-1422-3.

- Skutsch, Otto (1987). “Helen, her Name and Nature”. The Journal of Hellenic Studies 107: 188-193. doi:10.2307/630087. JSTOR 630087.

- Suzuki, Mihoko (1992). “The Iliad”. Metamorphoses of Helen. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-8080-9.

- Thompson, Diane P. (2004). “The Fall of Troy – The Beginning of Greek History”. The Trojan War. McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-1737-4.

- Whitby, Michael (2002). “Introduction”. Sparta. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-415-93957-7.