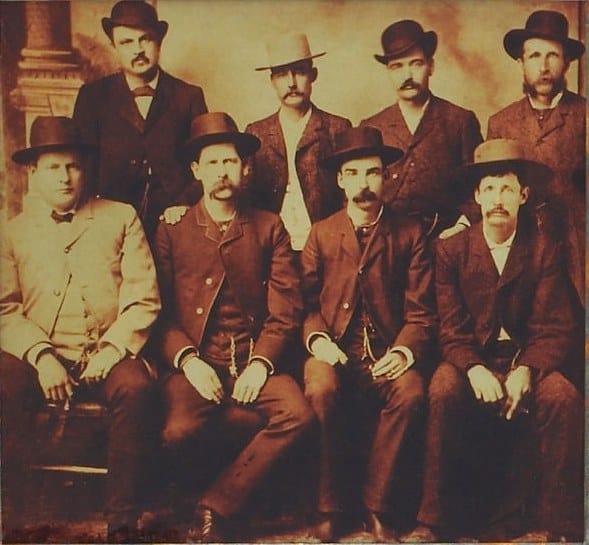

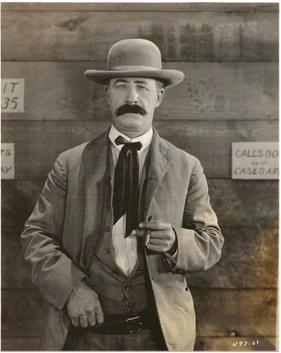

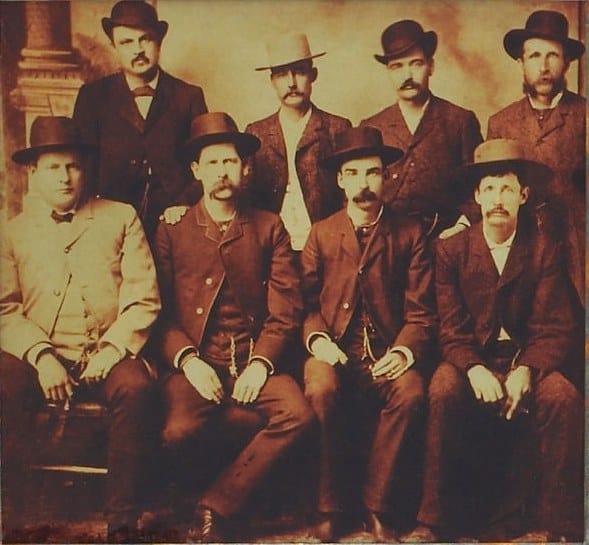

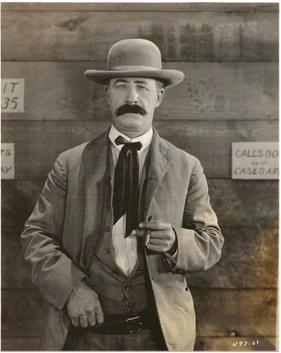

Wyatt Berry Stapp Earp (March 19, 1848 – January 13, 1929) was an American gambler, Pima County, Arizona Deputy Sheriff, and Deputy Town Marshal in Tombstone, Arizona, who took part in the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, during which lawmen killed three outlaw Cowboys. He is often regarded as the central figure in the shootout in Tombstone, although his brother Virgil was Tombstone City Marshal and Deputy U.S. Marshal that day, and had far more experience as a sheriff, constable, marshal, and soldier in combat.

Earp lived a restless life. He was at different times in his life a constable, city policeman, county sheriff, Deputy U.S. Sheriff, teamster, buffalo hunter, bouncer, saloon-keeper, gambler, brothel owner, pimp, miner, and boxing referee. Earp spent his early life in Iowa. His first wife Urilla Sutherland Earp died while pregnant, less than a year after they married. Within the next two years Earp was arrested, sued twice, escaped from jail, then was arrested three more times for “keeping and being found in a house of ill-fame”. He landed in the cattle boomtown of Wichita, Kansas, where he became a deputy city marshal for one year and developed a solid reputation as a lawman. In 1876, he followed his brother James to Dodge City, Kansas, where he became an assistant city marshal. In winter 1878, he went to Texas to gamble, where he met John Henry “Doc” Holliday, who Earp credited with saving his life.

Earp moved constantly throughout his life from one boomtown to another. He left Dodge City in 1879 and moved to Tombstone with his brothers James and Virgil, where a silver boom was underway. The Earps bought an interest in the Vizina mine and some water rights. There, the Earps clashed with a loose federation of outlaws known as the Cowboys. Wyatt, Virgil, and their younger brother Morgan held various law enforcement positions that put them in conflict with Tom and Frank McLaury, and Ike and Billy Clanton, who threatened to kill the Earps. The conflict escalated over the next year, culminating on October 26, 1881 in the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, in which the Earps and Holliday killed three of the Cowboys. In the next five months, Virgil was ambushed and maimed, and Morgan was assassinated. Pursuing a vendetta, Wyatt, his brother Warren, Holliday, and others formed a federal posse that killed three of the Cowboys who they thought responsible. Wyatt was never wounded in any of the gunfights, unlike his brothers Virgil and James or Doc Holliday, which only added to his mystique after his death.

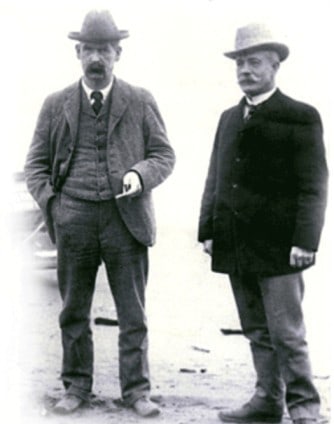

Wyatt was a lifelong gambler and was always looking for a quick way to make money. After meeting again in San Francisco, Earp and his third wife Josephine Earp joined a gold rush to Eagle City, Idaho, where they had mining interests and a saloon. They left there to race horses and open a saloon during a real estate boom in San Diego, California. Back in San Francisco, Wyatt raced horses again, but his reputation suffered irreparably when he refereed the Fitzsimmons-Sharkey boxing match and called a foul that led everyone to believe that he fixed the fight. They moved briefly to Yuma, Arizona before they next followed the Alaskan Gold Rush to Nome, Alaska, where they opened the biggest saloon in town. After making a large sum of money there, they opened another saloon in Tonopah, Nevada, the site of a new gold find. And finally, in about 1920, they worked on several mining claims in Vidal, California, retiring in the hot summers to Los Angeles.

When Earp died in 1929, he was well known for his notorious handling of the Fitzsimmons-Sharkey fight along with the O.K. Corral gun fight. An extremely flattering, largely fictionalized biography was published in 1931 after his death, becoming a bestseller and creating his reputation as a fearless lawman. Since then, Wyatt Earp has been the subject of and model for numerous films, TV shows, biographies, and works of fiction that have increased his mystique. Earp’s modern-day reputation is that of the Old West’s “toughest and deadliest gunman of his day”. Until the book was published, Earp had a dubious reputation as a minor figure in Western history. In modern times, Wyatt Earp has become synonymous with the stereotypical image of the Western lawman, and is a symbol of American frontier justice.

Early life

Wyatt was born on March 19, 1848 to Nicholas Porter Earp and his second wife, Virginia Ann Cooksey. He was named after his father’s commanding officer in the Mexican-American War, Captain Wyatt Berry Stapp, of the 2nd Company Illinois Mounted Volunteers. Some evidence supports Wyatt Earp’s birthplace as 406 South 3rd Street in Monmouth, Illinois, though the street address is disputed by Monmouth College professor and historian William Urban. Monmouth is in Warren County in western Illinois. Wyatt had an elder half-brother from his father’s first marriage, Newton, and a half-sister Mariah Ann, who died at the age of ten months.

In March 1849 or in early 1850, Nicholas Earp joined about one hundred others for a trip to California, where he looked for good farm land. Nicholas decided to move to San Bernardino County in the southern part of the state. Their daughter Martha became ill and later died, so the family instead stopped and settled in Pella, Iowa. Their new farm consisted of 160 acres (0.65 km2), 7 miles (11 km) northeast of Pella, Iowa.

Nicholas and Virginia Earp’s last child was a daughter named Adelia, born in June 1861 in Pella. Newton, James, and Virgil joined the Union Army on November 11, 1861. Their father was busy recruiting and drilling local companies, and Wyatt and his two younger brothers Morgan and Warren were left in charge of tending 80-acre (32 ha) corn crop. Wyatt was only thirteen years old, too young to enlist, but he tried on several occasions to run away and join the army. Each time, his father found him and brought him home. James was severely wounded in Fredericktown, Missouri, and returned home in summer 1863. Newton and Virgil fought several battles in the east and later followed the family to California.

California

On May 12, 1864, Nicholas Earp organized a wagon train and headed to San Bernardino, California, arriving on December 17, 1864. By late summer 1865, Virgil found work as a driver for Phineas Banning’s Stage Coach Line in California’s Imperial Valley, and 16-year-old Wyatt assisted. In spring 1866, Wyatt became a teamster, transporting cargo for Chris Taylor. His assigned trail for 1866 – 1868 was from Wilmington, through San Bernardino then Las Vegas, Nevada, to Salt Lake City, Utah Territory.

In spring 1868, Earp was hired by Charles Chrisman to transport supplies for the construction of the Union Pacific Railroad. He learned gambling and boxing while working on the rail head in the Wyoming Territory. Earp developed a reputation officiating boxing matches and refereed a fight between John Shanssey and Mike Donovan on July 4, 1868 or 1869 in Cheyenne, Wyoming.

Lawman

In spring 1868, the Earps moved east again to Lamar, Missouri, where Wyatt’s father Nicholas became the local constable. Wyatt rejoined the family the next year. Nicholas resigned as constable on November 17, 1869 to become the justice of the peace, and Wyatt was appointed constable in his place. On November 26, in return for his appointment, Earp filed a bond of $1,000. His sureties for this bond were his father, Nicholas Porter Earp; his paternal uncle, Jonathan Douglas Earp (April 28, 1824 – October 20, 1900); and James Maupin.

Marriage

In late 1869, Earp met Urilla Sutherland (c. 1849 – 1870), the daughter of hotelkeeper William and Permelia Sutherland, formerly of New York City. They married in Lamar on January 10, 1870, and in August 1870 bought a lot on the outskirts of town for $50. Urilla was pregnant and about to deliver their first child when she died from typhoid fever later that year. In November 1870, Earp sold the lot and a house on it for $75. He ran against his elder half-brother Newton for the office of constable, winning by 137 votes to Newton’s 108.

Lawsuits and charges

After Urilla’s death, Wyatt went through a downward spiral and had a series of legal problems. On March 14, 1871, Barton County filed a lawsuit against Earp and his sureties. Earp was in charge of collecting license fees for Lamar, which funded local schools, and he was accused of failing to turn in the fees. On March 31, James Cromwell filed a lawsuit against Earp, alleging that Earp had falsified court documents about the amount of money collected from Cromwell to satisfy a judgment. To make up the difference between what Earp turned in and Cromwell owed (which he claimed to have paid), the court seized Cromwell’s mowing machine and sold it for $38. Cromwell’s suit claimed that Earp owed him $75, the estimated value of the machine.

On March 28, 1871 Earp, Edward Kennedy, and John Shown were charged with stealing two horses, “each of the value of one hundred dollars”, from William Keys while in the Indian Country. On April 6, Deputy United States Marshal J. G. Owens arrested Earp for the horse theft. Commissioner James Churchill arraigned Earp on April 14, and set bail at $500. On May 15, an indictment was issued against Earp, Kennedy, and Shown. Anna Shown, John Shown’s wife, claimed that Earp and Kennedy got her husband drunk and then threatened his life to persuade him to help. On June 5 Edward Kennedy was acquitted while the case against Earp and John Shown remained. Earp didn’t wait for the trial. He climbed out through the roof of his jail and headed for Peoria, Illinois.

Peoria, Illinois

Years afterward, Wyatt’s biographer Stuart Lake wrote that Wyatt was hunting buffalo during the winter of 1871-72. But Earp was arrested three times in the Peoria area during that period. Earp is also listed in the Peoria city directory during 1872 as a resident in the house of Jane Haspel, who operated a brothel. In February 1872, Peoria police raided the brothel, arresting four women and three men: Wyatt and Morgan Earp, and George Randall. They were charged with “Keeping and being found in a house of ill-fame”. They were later fined twenty dollars plus costs for the criminal infraction. Wyatt Earp was arrested for the same crime on May 11 and again on September 10, 1872. The Peoria Daily National Democrat reported his September arrest aboard a floating brothel he owned, named the Beardstown Gunboat, with a woman named Sally Heckell, who called herself Wyatt Earp’s wife.

Some of the women are said to be good looking, but all appear to be terribly depraved. John Walton, the skipper of the boat and Wyatt Earp, the Peoria Bummer, were each fined $43.15. Sarah Earp, alias Sally Heckell, calls herself the wife of Wyatt Earp.

In that time period, “bummers” were “contemptible loafers who impose on hard-working citizens,” a “beggar,” and worse than tramps. They were men of poor character who were chronic lawbreakers.

Wichita, Kansas

Wyatt moved to the growing cow town of Wichita in early 1874, and local arrest records show that a prostitute named Sally Earp operated a brothel with the wife of his brother James from early 1874 to the middle of 1876. Wyatt may have been a pimp, but historian Robert Gary L. Roberts believes it more likely that he was an enforcer, or a bouncer for the brothel. It is possible that he hunted buffalo during 1873-74 before he went to Wichita. When the Kansas state census was completed in June 1875, Sally was no longer living with Wyatt, James, and Bessie.

Wichita was a railroad terminal and a destination for cattle drives from Texas. Like other frontier railroad terminals, when the cowboys accompanying the cattle drives arrived, the town was filled with drunken, armed cowboys celebrating the end of their long journey. Lawmen were kept busy. When the cattle drives ended and the cowboys left, Earp searched for something else to do. A newspaper story in October 1874 reported that he earned some money helping an off-duty police officer find thieves who had stolen a man’s wagon. Earp officially joined the Wichita marshal’s office on April 21, 1875, after the election of Mike Meagher as city marshal (or police chief), making $100 per month. He also dealt faro at the Long Branch Saloon. In late 1875, the Wichita Beacon newspaper published this story:

On last Wednesday (December 8), policeman Earp found a stranger lying near the bridge in a drunken stupor. He took him to the ‘cooler’ and on searching him found in the neighborhood of $500 on his person. He was taken next morning, before his honor, the police judge, paid his fine for his fun like a little man and went on his way rejoicing. He may congratulate himself that his lines, while he was drunk, were cast in such a pleasant place as Wichita as there are but a few other places where that $500 bank roll would have been heard from. The integrity of our police force has never been seriously questioned.

Earp was embarrassed in early 1876 when his loaded single-action revolver fell out of his holster while he was leaning back on a chair and discharged when the hammer hit the floor. The bullet went through his coat and out through the ceiling.

Wyatt’s stint as Wichita deputy came to a sudden end on April 2, 1876, when Earp took too active an interest in the city marshal’s election. According to news accounts, former marshal Bill Smith accused Wyatt of using his office to help hire his brothers as lawmen. Wyatt got into a fistfight with Smith and beat him. Meagher was forced to fire Earp and arrest him for disturbing the peace, which ended a tour of duty that the papers called otherwise “unexceptionable”. Meagher won the election, but the city council was split evenly on re-hiring Earp. His brother James opened a brothel in Dodge City, and Wyatt left Wichita to join him.

Dodge City, Kansas

After 1875, Dodge City became a major terminal for cattle drives from Texas along the Chisholm Trail. Earp was appointed assistant marshal in Dodge City under Marshal Lawrence “Larry” Deger around May 1876. There is evidence that Earp spent the winter of 1876 – 77 in another boomtown, Deadwood, Dakota Territory. He was not on the police force in Dodge City in late 1877, and rejoined the force in spring 1878 at the request of mayor James H. “Dog” Kelley. The Dodge City newspaper reported in July 1878 that Earp had been fined $1 for slapping a muscular prostitute named Frankie Bell, who (according to the papers) “heaped epithets upon the unoffending head of Mr. Earp to such an extent as to provide a slap from the ex-officer”. Bell spent the night in jail and was fined $20, while Earp’s fine was the legal minimum.

In October 1877, outlaw Dave Rudabaugh robbed a Sante Fe Railroad construction camp and fled south. Earp was given a temporary commission as Deputy U.S. Marshal and he left Dodge City, following Rudabaugh over 400 miles (640 km) towards Fort Griffin, Texas. He arrived at the frontier town on the Clear Fork of the Brazos River. Earp went to the Bee Hive Saloon, the largest in town and owned by John Shanssey, who Earp had known since he was 21. Shanssey told Earp that Rudabaugh had passed through town earlier in the week, but he didn’t know where he was headed. Shanssey suggested that Earp ask gambler “Doc” Holliday, who had played cards with Rudabaugh. Holliday told Earp that Rudabaugh had headed back into Kansas.

In early 1878, Earp returned to Dodge City, where he become the assistant city marshal, serving under Charlie Bassett. Doc Holliday with his common-law wife Big Nose Kate also showed up in Dodge City during the summer of 1878. During the summer, Ed Morrison and other Texas cowboys rode into Dodge and shot up the town, galloping down Front Street. They entered the Long Branch Saloon, vandalized the room, and harassed the customers. Hearing the commotion, Wyatt burst through the front door into a bunch of guns pointing at him. Holliday was playing cards in the back and put his pistol at Morrison’s head, forcing him and his men to disarm. Earp credited Holliday with saving his life that day, and he and Earp became friends.

While in Dodge City, he became acquainted with James and Bat Masterson, Luke Short, and prostitute Celia Anne “Mattie” Blaylock. Blaylock became Earp’s common-law wife until 1881. Earp resigned from the Dodge City police force on September 9, 1879, and she accompanied him to Las Vegas in New Mexico Territory, and then to Tombstone in Arizona Territory.

George Hoyt shooting

At about 3:00 in the morning of July 26, 1878, George Hoyt (spelled in some accounts as “Hoy”) and other drunken cowboys shot their guns wildly, including three shots into Dodge City’s Comique Theater, causing comedian Eddie Foy to throw himself to the stage floor in the middle of his act. Fortunately, no one was injured. Assistant Marshal Earp and policeman Bat Masterson responded and “together with several citizens, turned their pistols loose in the direction of the fleeing horsemen”. As the riders crossed the Arkansas river bridge south of town, George Hoyt fell from his horse after he was wounded in the arm or leg. Earp told Stuart Lake that he saw Hoyt through his gun sights against the morning horizon and fired the fatal shot, killing him that day, but the Dodge City Times reported that Hoyt developed gangrene and died on August 21 after his leg was amputated.

Move to Tombstone, Arizona

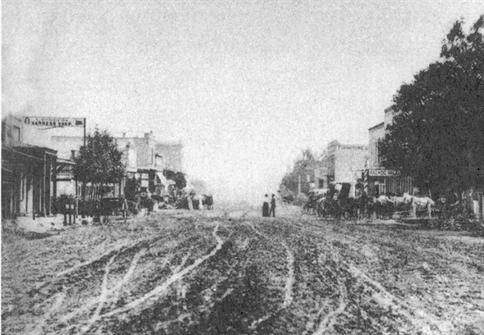

In 1879, Wyatt received a letter from his older brother Virgil, who was the town constable in Prescott, Arizona Territory. Virgil wrote Wyatt about the opportunities in the silver-mining boomtown of Tombstone. In September 1879, Wyatt resigned as assistant marshal in Dodge City. Accompanied by his common-law wife Mattie Blaylock, his brother Jim and his wife Bessie, they left for Arizona Territory. They stopped in Las Vegas, New Mexico, where they reunited with Doc Holliday and his common-law wife Big Nose Kate. The five of them arrived in Prescott in November. Wyatt, Virgil, and James Earp with their wives arrived in Tombstone on December 1, 1879, although Doc remained in Prescott, where the gambling afforded better opportunities. Later in life, Wyatt wrote that “In 1879 Dodge was beginning to lose much of the snap which had given it a charm to men of reckless blood, and I decided to move to Tombstone, which was just building up a reputation.”

On November 27, 1879, three days before moving to Tombstone, Virgil was appointed by Crawley Dake, U.S. Marshal for the Arizona Territory, as Deputy U.S. Marshal for the Tombstone mining district, some 280 miles (450 km) from Prescott. As Deputy U.S. Marshal in Tombstone, Virgil Earp represented federal authority in the southeast area of the Arizona Territory.

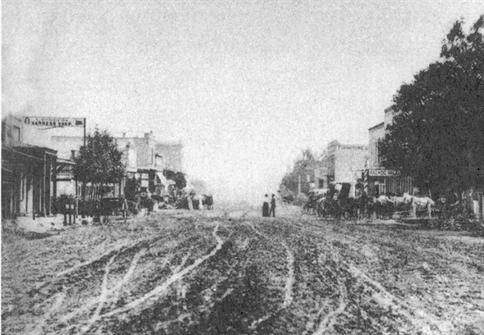

On March 5, 1879, when the city of Tombstone was founded, it had about 100 people living in tents and a few shacks. By the time the Earps arrived nine months later on December 1, it had grown to about 1,000 residents. Wyatt brought horses and a buckboard wagon, which he planned to convert into a stagecoach, but on arrival he found two established stage lines already running. In Tombstone, the Earps staked mining claims and water rights interests, attempting to capitalize on the mining boom. Jim worked as a barkeep. On December 6, 1879, the three Earps and Robert J. Winders filed a location notice for the First North Extension of the Mountain Maid Mine. When none of their business interests proved fruitful, Wyatt was hired in April or May 1880 by Wells, Fargo & Co. agent Frederick James Dodge as a shotgun messenger on stagecoaches when they transported Wells Fargo strongboxes. In summer 1880, younger brothers Morgan arrived from Montana and Warren Earp moved to Tombstone as well. In September, Wyatt’s friend Doc Holliday arrived from Prescott.

First confrontation with the Cowboys

On July 25, 1880, U.S. Army Captain Joseph H. Hurst asked Deputy U.S. Marshal Virgil Earp to assist him in tracking Cowboys who had stolen six U.S. Army mules from Camp Rucker. Virgil requested the assistance of his brothers Wyatt and Morgan, along with Wells Fargo agent Marshall Williams, and they found the mules at the McLaurys’ ranch. McLaury was a Cowboy, a term which in that time and region was generally used to refer to a loose association of outlaws, some of whom also were landowners and ranchers. Legitimate cowmen were referred to as cattle herders or ranchers. They found the branding iron used to change the “U.S.” brand to “D.8.” Stealing the mules was a federal offense because the animals were U.S. property.

Cowboy Frank Patterson “made some kind of a compromise” with Captain Hurst, who persuaded the posse to withdraw, with the understanding that the mules would be returned. The Cowboys showed up two days later without the mules and laughed at Hurst and the Earps. In response, Capt. Hurst printed a handbill describing the theft, and specifically charged Frank McLaury with assisting with hiding the mules. He also reproduced the flyer in The Tombstone Epitaph, on July 30, 1880. Frank McLaury angrily printed a response in the Cowboy-friendly Nuggett, calling Hurst “unmanly”, “a coward, a vagabond, a rascal, and a malicious liar”, and accused Hurst of stealing the mules himself. Capt. Hurst later cautioned Wyatt, Virgil, and Morgan that the Cowboys had threatened their lives. Virgil reported that Frank accosted him and warned him “If you ever again follow us as close as you did, then you will have to fight anyway.” A month later Earp ran into Frank and Tom McLaury in Charleston, and they told him if he ever followed them as he had done before, they would kill him.

Becomes deputy sheriff

On July 28, 1880, Wyatt was appointed Deputy Sheriff for the eastern part of Pima County, which included Tombstone, by Democratic County Sheriff Charlie Shibell. Wyatt passed on his Wells Fargo job as shotgun messenger to his brother Morgan. Wyatt did his job well, and from August through November his name was mentioned nearly every week by the The Tombstone Epitaph or the Nugget newspapers.

The deputy sheriff’s position was worth more than US$40,000 a year (about $977,517 today) because he was also county assessor and tax collector, and the board of supervisors allowed him to keep ten percent of the amounts paid. While Wyatt was Deputy Sheriff, former Democrat state legislator Johnny Behan arrived in September 1880.

Loses reappointment

Wyatt only served as deputy sheriff for eastern Pima County for about three months because, in November, Democrat Shibell ran for re-election against Republican challenger Bob Paul. The region was strongly Republican and Paul was expected to win. Republican Wyatt expected he would continue in the job. Given how fast eastern Pima County was growing, everyone expected that it would be split off into its own county soon with Tombstone as its seat. Wyatt hoped to win the job as the new county sheriff and continue receiving the plum 10% of all tax moneys collected. Southern Pacific was the major landholder, so that tax collection was a relatively easy process.

On election day, November 2, Precinct 27 in the San Simon Valley in northern Cochise County, turned out 104 votes, 103 of them for Shibell. Shibell unexpectedly won the election by a margin of 58 votes under suspicious circumstances.

James C. Hancock reported that Cowboys Curly Bill Brocius and Johnny Ringo served as election officials in the San Simon precinct. However, on November 1, the day before the election, Ringo biographer David Johnson places Ringo in New Mexico with Ike Clanton. Curly Bill had been arrested and jailed in Tucson on October 28 for shooting Sheriff Fred White, and he was still there on election day.

The home of John Magill was used as the polling place. The precinct only contained about 10 eligible voters (another source says 50), but the Cowboys gathered non-voters like the children and Chinese and had them cast ballots. Not satisfied, they named all the dogs, burros and poultry and cast ballots in their names for Shibell. The election board met on November 14 and declared Shibell as the winner.

On November 19, Republican Paul decided to contest the election results and Wyatt worked to help overturn the results. Earp resigned from the Sheriff’s office on November 9, 1880, and Shibell immediately appointed Behan as the new Deputy Sheriff for eastern Pima County. Democrat Johnny Behan had considerably more political experience than Republican Wyatt Earp. Behan had previously served as Yavapai County Sheriff from 1871 to 1873. He had been elected to the Arizona Territorial Legislature twice, representing Yavapai Country in the 7th Territorial Legislature in 1873 and Mohave County in the 10th in 1879. Behan moved for a time to the northwest Arizona Territory, where he served as the Mohave County Recorder in 1877 and then deputy sheriff of Mohave County at Gillet, in 1879.

Paul filed a lawsuit on November 19 contesting the election results, alleging that Shibell’s Cowboy supporters Iike Clanton, Curly Bill Brocius, and Frank McLaury had cooperated in ballot stuffing. Judge C.G.W. French ruled in Paul’s favor in late January 1881, but Shibell appealed. His lawsuit was finally resolved by April 1881. The election commission found that a mysterious “Henry Johnson” was responsible for certifying the ballots. This turned out to be James Johnson, the same James K. Johnson who had been shooting up Allen Street the night Marshal White was killed. Moreover, he was the same Johnson that testified at Curly Bill’s preliminary hearing after he shot Fred White. James Johnson later testified for Bud Paul in the election hearing and said that the ballots had been left in the care of Phin Clanton. None of the witnesses during the election hearing reported on ballots being cast for dogs. The recount found Paul had 402 votes and Shibell had 354. Sixty-two were kept from a closer examination. Paul was declared the winner of the Pima County sheriff election but by that time the election was a moot point. Paul could not replace Behan with Earp because on January 1, 1881, Cochise County was created out of the eastern portion of Pima County.

Behan wins election

Earp and Behan both applied to fill the new position of Cochise County sheriff, which like the Pima County Sheriff job paid the office holder 10% of the fees and taxes collected. Earp thought he had a good chance to win the position because he was the former undersheriff in the region and a Republican, like Arizona Territorial Governor John C. Fremont. However, Behan had greater political experience and influence in Prescott.

Earp improbably testified during the preliminary hearing after the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral that he and Behan had made a deal. If Earp withdrew his application to the legislature, Behan agreed to appoint Earp as undersheriff. Behan received the appointment in February 1881, but did not keep his end of the bargain and instead chose Harry Woods, a prominent Democrat, as undersheriff. Behan testified at first that he had not made any deal with Earp, although he later admitted he had lied. Behan said he broke his promise to appoint Earp because of an incident that occurred shortly before his appointment.

This incident arose after Earp learned that one of his prize horses, stolen more than a year before, was in the possession of Ike Clanton and his brother Billy. Earp and Holliday rode to the Clanton ranch near Charleston to recover the horse. On the way, they overtook Behan, who was riding in a wagon. Behan was also heading to the ranch to serve an election-hearing subpoena on Ike Clanton. Accounts differ as to what happened next. Earp later testified that when he arrived at the Clanton ranch, Billy Clanton gave up the horse even before being presented with ownership papers. According to Behan’s testimony, however, Earp had told the Clantons that Behan was on his way to arrest them for horse theft. After the incident, which embarrassed both the Clantons and Behan, Behan testified that he did not want to work with Earp and chose Woods instead.

Conflicts with Sheriff Behan

In the personal arena, 32-year-old Wyatt Earp and 35-year-old Johnny Behan shared an interest in the same 18-year-old woman, Josephine Sarah Marcus. She said she first visited Tombstone as part of the Pauline Markham Theatre Troupe on December 1, 1879 for a one-week engagement but modern researchers have not found any record that she was ever part of the theater company. Behan owned a saloon in Top Top, where he maintained a prostitute named Sadie Mansfield. In September 1880, Behan moved to Tombstone. Sadie may have returned to San Francisco and then joined Behan in Tombstone, where she and Behan continued their relationship. Sadie was a well-known nickname for Sarah, and it was common for prostitutes to change their first name.

In spring 1881, Marcus found Behan in bed with the wife of a friend and kicked him out, although she still used the Behan surname through the end of that summer. Earp had a common-law relationship with Mattie Blaylock, who was listed as his wife in the June 1880 census. She suffered from severe headaches and became addicted to laudanum, a commonly used opiate and painkiller. There are no contemporary records in Tombstone of a relationship between Josephine and Earp, but Behan and Earp both had offices above the Crystal Palace Saloon.

Marcus and Wyatt went to great lengths to sanitize their history. For example, they worked hard to keep both her name and the name of Wyatt’s second wife Mattie out of Stuart Lake’s 1931 book, Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal, and Marcus threatened litigation to keep it that way. Marcus also told Earp’s biographers and others that Earp never drank, didn’t own gambling saloons, and that he never provided prostitutes to customers, although all were true.

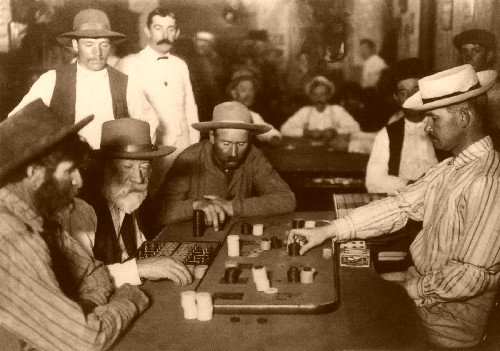

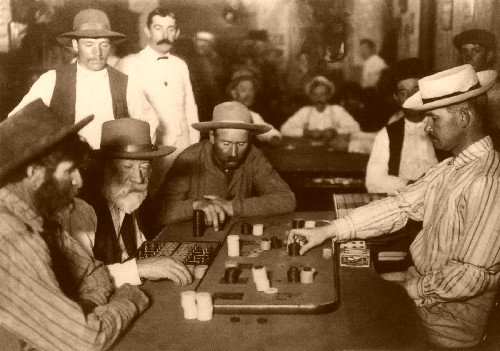

Interest in mining and gambling

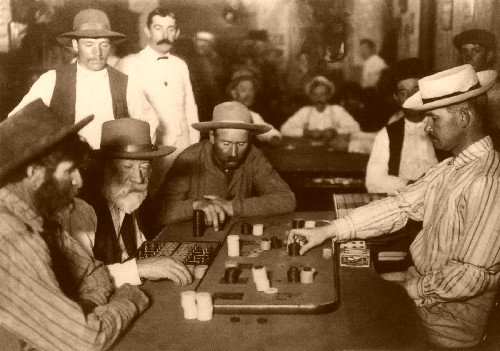

Losing the undersheriff position left Wyatt Earp without a job in Tombstone; however, Wyatt and his brothers were beginning to make some money on their mining claims in the Tombstone area. In January 1881, Oriental Saloon owner Mike Joyce gave Wyatt Earp a one-quarter interest in the faro concession at the Oriental Saloon in exchange for his services as a manager and enforcer. Gambling was regarded as a legitimate profession, comparable to a doctor or member of clergy, at the time. Wyatt invited his friend, lawman and gambler Bat Masterson, to Tombstone to help him run the faro tables in the Oriental Saloon. In June 1881, Wyatt also telegraphed another friend and gambler from Dodge, Luke Short, who was living in Leadville, Colorado, and offered him a job as a faro dealer.

Bat remained until April 1881, when he returned to Dodge City to assist his brother Jim. On October 8, 1881, Doc Holliday got into a dispute with John Tyler in the Oriental Saloon. A rival gambling concession operator hired Tyler to make trouble at the Oriental and disrupt Wyatt’s business. When Tyler started a fight after losing a bet, Wyatt threw him out of the saloon. Holliday later wounded Oriental owners Milt Joyce and his partner Lou Rickabaugh and was convicted of assault.

Stands down lynch mob

Stuart Lake described Earp single-handedly standing down a large crowd that wanted to lynch gambler Michael O’Rourke (Johnny Behind the Deuce), after O’Rourke had killed Henry Schneider, chief engineer of the Tombstone Mining and Milling Company–he said in self-defense. Henry was well-liked and a mob of miners quickly gathered, threatening to lynch O’Rourke on the spot. This incident added to Earp’s modern legend as a lawman. While Lake gave Wyatt exclusive credit for saving O’Rourke, in fact Wyatt had acted with nerve in the situation, but Ben Sippy, Johnny Behan, and Virgil Earp deserved the majority of the credit.

Cowboys rob stagecoaches

Tensions between the Earps and both the Clantons and McLaurys increased through 1881. On March 15, 1881, at 10 p.m., three cowboys attempted to rob a Kinnear & Company stagecoach reportedly carrying US$26,000 in silver bullion (or about $635,386 in today’s dollars). The amount of bullion actually carried has been questioned by modern researchers, who note that at the then current value of US$1.00 per ounce, the bullion would have weighed about 1,600 pounds (730 kg), a significant weight for a team of horses. The hold up took place near Benson, during which the popular driver Eli “Budd” Philpot and passenger Peter Roerig were killed.

The Earps and a posse tracked the men down and arrested Luther King, who confessed he had been holding the reins for Bill Leonard, Harry “The Kid” Head, and Jim Crane as the robbers. King was arrested and Sheriff Johnny Behan escorted him to jail, but somehow King walked in the front door and almost immediately out the back door.

During the hearing into the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, Wyatt testified that he offered the US$3,600 in Wells Fargo reward money ($1,200 per robber) to Ike Clanton and Frank McLaury in return for information about the identities of the three robbers. Wyatt testified that he had other motives for his plan as well: he hoped that arresting the murderers would boost his chances for election as Cochise County sheriff.

According to both Wyatt and Virgil, Frank McLaury and Ike Clanton both agreed to provide information to assist in their capture, but never had a chance to fulfill the agreement. All three cowboy suspects in the stage robbery were killed when attempting other robberies. Wyatt told the court at the hearing after the O.K. Corral shootout that he had taken the extra step of obtaining a second copy of a telegram for Ike from Wells Fargo assuring that the reward for capturing the killers applied either dead or alive.

In his testimony at the court hearing, Clanton said Wyatt didn’t want to capture the men, but to kill them. Clanton said Earp wanted to conceal the Earp’s involvement in the Benson stage robbery. He said Wyatt swore him to secrecy and the next day Morgan Earp had asked him whether he would make the agreement with Wyatt. He said that four or five days afterward Morgan had confided in him that he and Wyatt had “piped off $1,400 to Doc Holliday and Bill Leonard” who were supposed to be on the stage the night Bud Philpot was killed. During his testimony, Clanton told the court “I was not going to have anything to do with helping to capture–” and then he corrected himself “–kill Bill Leonard, Crane and Harry Head”. Clanton denied having any knowledge of the Wells Fargo telegram confirming the reward money.

September stagecoach robbery

Meanwhile, tensions between the Earps and the McLaurys increased with the holdup of a passenger stage on the Sandy Bob Line in the Tombstone area on September 8, bound for nearby Bisbee. The masked robbers shook down the passengers and robbed the strongbox. They were recognized by their voices and language. They were identified as Deputy Sheriff Pete Spence (an alias for Elliot Larkin Ferguson) and Deputy Sheriff Frank Stilwell, a business partner of Spence. Stilwell was fired a short while later as a Deputy Sheriff for Sheriff Behan (for county tax “accounting irregularities”). Spence and Stilwell were friends of the McLaury brothers. Wyatt and Virgil Earp rode with the sheriff’s posse attempting to track the Bisbee stage robbers, and Wyatt discovered an unusual boot heel print in the mud. They checked with a shoemaker in Bisbee and found a matching heel that he had just removed from Stilwell’s boot. A further check of a Bisbee corral turned up both Spence and Stilwell. Stilwell and Spence were arrested by sheriff’s deputies Breakenridge and Nagel for the stage robbery, and later by Deputy U.S. Marshal Virgil Earp on the federal offense of mail robbery.

They were arraigned before Justice Wells Spicer who set their bail at $7,000 each. They were released after paying their bail, but Spence and Stilwell were re-arrested by Virgil for the Bisbee robbery a month later, on October 13, on the new federal charge of interfering with a mail carrier. The newspapers, however, reported that they had been arrested for a different stage robbery that occurred (October 8) near Contention City. Occurring less than two weeks before the O.K. Corral shootout, this final incident may have been misunderstood by the McLaurys. While Wyatt and Virgil were still out of town for the Spence and Stilwell hearing, Frank McLaury confronted Morgan Earp, telling him that the McLaurys would kill the Earps if they tried to arrest Spence, Stilwell, or the McLaurys again.

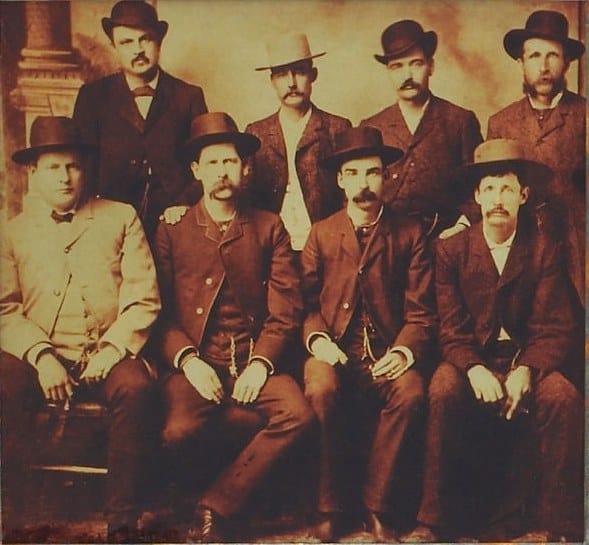

Gunfight on Fremont Street

On Wednesday, October 26, 1881, the tension between the Earps and the Cowboys came to a head. Ike Clanton, Billy Claiborne, and other Cowboys had been threatening to kill the Earps for several weeks. Tombstone city Marshal Virgil Earp learned that the Cowboys were armed and had gathered near the O.K. Corral. He asked Wyatt and Morgan Earp and Doc Holliday to assist him, as he intended to disarm them. Wyatt was acting as a temporary assistant marshal, Morgan was a Deputy City Marshal, and Virgil deputized Holliday for the occasion. At approximately 3 p.m. the Earps headed towards Fremont Street, where the Cowboys had been reported gathering.

They confronted five Cowboys in a vacant lot adjacent to the O.K. Corral’s rear entrance on Fremont Street. The lot between the Harwood House and Fly’s Boarding House and Photography Studio was narrow–the two parties were initially only about 6 to 10 feet (1.8 to 3.0 m) apart. Ike Clanton and Billy Claiborne fled the gunfight. Tom and Frank McLaury along with Billy Clanton stood their ground and were killed. Morgan was clipped by a shot across his back that nicked both shoulder blades and a vertebra. Virgil was shot through the calf and Holliday was grazed by a bullet.

Charged with murder

On October 30, as permitted by Territorial law, Ike Clanton filed murder charges against the Earps and Holliday. Justice Wells Spicer convened a preliminary hearing on October 31 to determine if there was enough evidence to go to trial. In an unusual proceeding, he took written and oral testimony from a number of witnesses over more than a month.

Sheriff Behan, testifying for the prosecution, said the Cowboys had not resisted but either thrown up their hands and turned out their coats to show they were not armed. He said that Tom McLaury threw open his coat to show that he was not armed and that the first two shots were fired by the Earp party. Sheriff Behan insisted Doc Holliday had fired first using a nickel-plated revolver, although other witnesses reported seeing him carrying a messenger shotgun immediately beforehand.

The Earps hired an experienced trial lawyer, Thomas Fitch, as defense counsel. Wyatt testified that he drew his gun only after Billy Clanton and Frank McLaury went for their pistols. He detailed the Earps’ previous troubles with the Clantons and McLaurys and explained that they intended to disarm the cowboys. He said they fired in self-defense. Fitch managed to produce testimony from prosecution witnesses during cross-examination that was contradictory and appeared to dodge his questions.

After extensive testimony, Justice Spicer ruled on November 30 that there was not enough evidence to indict the men. He said the evidence indicated that the Earps and Holliday acted within the law and that Holliday and Wyatt had been deputized temporarily by Virgil. Even though the Earps and Holliday were free, their reputations had been tarnished. Supporters of the Cowboys in Tombstone looked upon the Earps as robbers and murderers and plotted revenge.

Cowboys’ revenge

On December 28, while walking between saloons on Allen Street in Tombstone, Virgil was ambushed and maimed by a shotgun round that struck his left arm and shoulder. Ike Clanton’s hat was found in the back of the building across Allen Street from where the shots were fired. Wyatt wired U.S. Marshal Crawley P. Dake asking to be appointed deputy U.S. marshal with authority to select his own deputies. Dake granted the request in late January and provided the Earps with some funds he borrowed from Wells, Fargo & Co. on behalf of the Earps, variously reported as $500 to $3,000.

In mid-January, when Earp ally Rickabaugh sold the Oriental Saloon to Earp adversary Milt Joyce, Wyatt sold his gambling concessions at the hotel. The Earps also raised some funds from sympathetic business owners in town. On February 2, 1882, Wyatt and Virgil, tired of the criticism leveled against them, submitted their resignations to Dake, who refused to accept them because their accounts had not been settled. On the same day, Wyatt sent a message to Ike Clanton that he wanted to reconcile their differences, which Clanton refused. Clanton was also acquitted that day of the charges against him in the shooting of Virgil Earp, when the defense brought in seven witnesses who testified that Clanton was in Charleston at the time of the shooting.

The Earps needed more funds to pay for the extra deputies and associated expenses. Contributions received from supportive business owners were not enough. On February 13, Wyatt mortgaged his home to lawyer James G. Howard for $365.00 (about $8,920 today) and received $365.00 in U.S. gold coin. (He was never able to repay the loan and in 1884 Howard foreclosed on the house.)

After attending a theatre show on March 18, Morgan Earp was assassinated by gunmen firing from a dark alley through a door window into a room where he was playing billiards. Morgan was struck in the right side. The bullet shattered his spine, passed through his left side, and lodged in the thigh of George A. B. Berry. Another round narrowly missed Wyatt. A doctor was summoned and Morgan was moved from the floor to a nearby couch. The assassins escaped in the dark and Morgan died forty minutes later.

Wyatt Earp felt he could not rely on civil justice and decided to take matters into his own hands. He concluded that the only way to deal with Morgan’s assassins was to kill them all.

Earp vendetta

The day after Morgan’s assassination, Deputy U.S. Marshal Wyatt formed a posse made up of his brothers James and Warren, Doc Holliday, Sherman McMaster, Jack “Turkey Creek” Johnson, Charles “Hairlip Charlie” Smith, Daniel “Tip” Tipton, and John Wilson “Texas Jack” Vermillion to protect the family and pursue the suspects, paying them $5.00 a day. They took Morgan’s body to the railhead in Benson. James was to accompany Morgan’s body to the family home in Colton, California, where Morgan’s parents and wife waited to bury him. The posse guarded Virgil and Addie through to Tucson, where they had heard Frank Stilwell and other Cowboys were waiting to kill Virgil. The next morning Frank Stilwell’s body was found alongside the tracks riddled with buckshot and gunshot wounds. Wyatt and five other federal lawmen were accused of murdering him and Tucson Justice of the Peace Charles Meyer issued warrants for their arrest.

The Earp posse briefly returned to Tombstone, where Sheriff Behan tried to stop them. The heavily armed posse brushed him aside. Hairlip Charlie and Warren remained in Tombstone, and the rest set out for Pete Spence’s wood camp in the Dragoon Mountains. They found and killed Florentino “Indian Charlie” Cruz. Two days later, near Iron Springs (later Mescal Springs), in the Whetstone Mountains, they were seeking to rendezvous with a messenger for them. They unexpectedly stumbled onto the wood camp of Curly Bill Brocius, Pony Diehl, and other Cowboys. According to reports from both sides, the two sides immediately exchanged gun fire. Except for Wyatt and Texas Jack Vermillion, whose horse was shot, the Earp party withdrew to find protection from the heavy gunfire. Curly Bill fired at Wyatt with a shotgun but missed. Eighteen months prior Wyatt had protected Curly Bill against a mob ready to lynch him and then provided testimony that helped spare Curly Bill from a murder trial for killing Sheriff Fred White. Now, Wyatt returned Curly Bill’s gunfire with his own shotgun and shot Curly Bill in the chest from about 50 feet (15 m) away. Curly Bill fell into the water by the edge of the spring and died.

Wyatt received bullet holes in both sides of his long coat and another struck his boot heel. After emptying his shotgun, Wyatt fired his pistol, mortally wounding Johnny Barnes in the chest and wounded Milt Hicks in the arm. Vermillion tried to retrieve his rifle wedged in the scabbard under his fallen horse, exposing himself to the Cowboys’ gunfire. Doc Holliday helped him get to cover. Wyatt had trouble remounting his horse because his cartridge belt had slipped down his legs. He was finally able to get on his horse and with the rest of the posse retreated.

The Earp Party rode north to the Percy Ranch, but were not welcomed by Hugh and Jim Percy, who feared the Cowboys; after a meal and some rest, they left at about 3:00 in the morning of March 27. The Earp party slipped into the area near Tombstone and met with supporters, including “Hairlip Charlie” Smith and Warren Earp. On March 27, the posse arrived at the Sierra Bonita Ranch owned by Henry C. Hooker, a wealthy and prominent rancher. That night Dan Tipton caught the first stage out of Tombstone and headed for Benson, carrying $1,000 from mining owner and Earp supporter E. B. Gage for the posse. Hooker congratulated Earp on the killing of Curly Bill. Hooker fed them and Wyatt told him he wanted to buy new mounts. Hooker was known for his purebred stallions and ran over 500 brood mares that produced horses that became known for their speed, beauty and temperament. He provided Wyatt and his posse with new mounts but refused to take Wyatt’s money. When Behan’s posse was observed in the distance, Hooker suggested Wyatt make his stand there, but Wyatt moved into the hills about three miles (5 km) distant near Reilly Hill.

The federal posse led by Wyatt Earp wasn’t found by the local posse, led by Cochise County Sheriff John Behan, although Behan’s party trailed the Earps for many miles. In the middle of April 1882 the Earp party left the Arizona Territory and headed east into New Mexico Territory and then into Colorado.

The coroner reports credited the Earp party with killing four men–Frank Stilwell, Curly Bill, Indian Charlie, and Johnny Barnes–in their two-week-long ride. In 1888 Wyatt Earp gave an interview to California historian H. H. Bancroft during which he claimed to have killed “over a dozen stage robbers, murderers, and cattle thieves” in his time as a lawman.

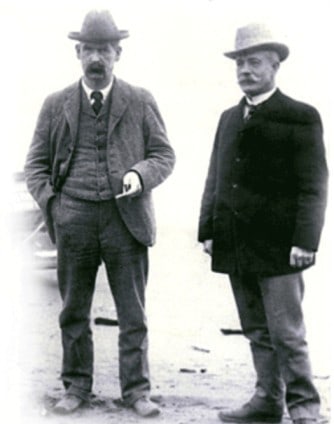

Life after Tombstone

The gunfight in Tombstone lasted only 30 seconds, but it would end up defining Earp for the rest of his life. After Wyatt killed Frank Stilwell in Tucson, his movements received national press coverage and he became a known commodity in Western folklore.

After killing the four Cowboys, Wyatt and Warren Earp, Holliday, Sherman McMaster, “Turkey Creek” Jack Johnson, and Texas Jack Vermillion left Arizona. They stopped in Albuquerque, New Mexico, where they met Deputy U.S. Marshal Bat Masterson, Wyatt’s friend. Masterson went with them to Trinidad, Colorado, where Masterson owned a saloon. Wyatt dealt Faro for several weeks before he, Warren, and possibly Dan Tipton arrived in May 1882 in Gunnison, Colorado. Holliday headed to Pueblo and then Denver. The Earps and Texas Jack set up camp on the outskirts of Gunnison, where they remained quietly at first, rarely going into town for supplies. Eventually, Wyatt took over a faro game at a local saloon. They were also reported to have pulled a “gold brick scam” on a German visitor named Ritchie by trying to sell him gold-painted rocks for $2,000.

Wyatt left the house they owned in Tombstone to his common-law wife Mattie Blaylock, but she waited for him in Colton, where his parents and Virgil were living. She eventually accepted that Wyatt was not coming for her and moved to Pinal City, Arizona, where she resumed life as a prostitute. Mattie struggled with addictions and committed “suicide by opium poisoning” on July 3, 1888.

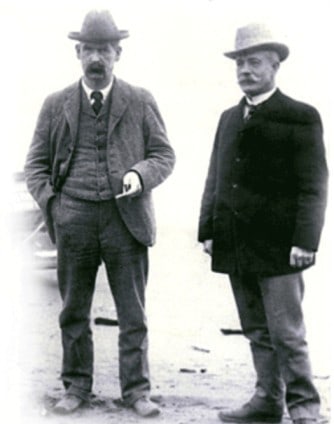

Joins Josephine in San Francisco

Sadie, traveling as either Mrs. J. C. Earp or Mrs. Wyatt Earp, left for Los Angeles on March 25, 1882, and then returned to her family in San Francisco. In July 1882, Wyatt went to San Francisco and joined Sadie and his brother Virgil. In early 1883, Sadie and Earp left San Francisco for Gunnison, where Earp ran a Faro bank until he received a request for assistance from Luke Short in Dodge City. Sadie was his common-law wife for the next 46 years.

Dodge City War

On May 31, 1883, Earp and Sadie along with Bat Masterson arrived in Dodge City to help Luke Short, part owner of the Long Branch saloon, during what became known as the Dodge City War. When the Mayor tried to run Luke Short first out of business and then out of town, Short appealed to Masterson who contacted Earp. While Short was discussing the matter with Governor George Washington Glick in Kansas City, Earp showed up with Johnny Millsap, Shotgun John Collins, Texas Jack Vermillion, and Johnny Green. They marched up Front Street into Short’s saloon, where they were sworn in as deputies by constable “Prairie Dog” Dave Marrow. The town council offered a compromise to allow Short to return for ten days to get his affairs in order, but Earp refused to compromise. When Short returned, there was no force ready to turn him away. Short’s Saloon reopened, and the Dodge City War ended without a shot being fired.

Idaho mining venture

In 1884, Wyatt and his wife Josie, his brothers Warren and James, and James’ wife Bessie arrived in Eagle City, Idaho, another new boomtown that was created as a result of the discovery of gold, silver, and lead in the Coeur d’Alene area. (It’s now a ghost town in Shoshone County). Wyatt joined the crowd looking for gold in the Murray-Eagle mining district. They paid $2,250 for a 50 feet (15 m) diameter white circus, in which they opened a dance hall and saloon called The White Elephant. An advertisement in a local newspaper suggests gentlemen ‘come and see the elephant’.

Earp was named Deputy Sheriff in the area including newly incorporated Kootenai County, Idaho, which was disputing jurisdiction of Eagle City with Shoshone County. There were a considerable number of disagreements over mining claims and property rights, which Earp had a part in. On March 28, several feet of snow were still on the ground. Bill Buzzard, a miner of dubious reputation, began constructing a building when one of Wyatt’s partners, Jack Enright, tried to stop the construction. Enright claimed the building was on part of his property. Words were exchanged and Buzzard reached for his Winchester. He fired several shots at Enright and a skirmish developed. Allies of both sides quickly took defensive positions between snowbanks and began shooting at one another. Deputy Sheriff Wyatt Earp and his brother James stepped into the middle of the fray and helped peacefully resolve the dispute before anyone was seriously hurt. Shoshone County Deputy W. E. Hunt then arrived and ordered the parties to turn over their weapons.

In about April 1885, it was reported that Wyatt Earp used his badge to join a band of claim jumpers in Embry Camp, later renamed Chewelah, Washington. Within six months their substantial stake had run dry, and the Earps left the Murray-Eagle district. About 10 years later, after the Fitzimmons-Sharkey fight, a reporter hunted up Buzzard and extracted a story from him that accused Wyatt of being the brains behind lot-jumping and a real-estate fraud, further tarnishing his reputation.

San Diego real estate boom

After the Coeur d’Alene mining venture died out, Earp and Josie briefly went to El Paso, Texas before moving in 1887 to San Diego, where the railroad was about to arrive and a real estate boom was underway. They stayed for about four years, living most of the time in the Brooklyn Hotel. Earp speculated in San Diego’s booming real estate market. Between 1887 and around 1896 he bought four saloons and gambling halls, one on Fourth Street and the other two near Sixth and E, all in the “respectable” part of town. They offered 21 games including faro, blackjack, poker, keno, and other Victorian-American games of chance like pedro and monte. At the height of the boom, he made up to $1,000 a night in profit. Wyatt also owned the Oyster Bar located in the first granite-faced building in San Diego, the four-story Louis Bank Building at 837 5th Avenue, one of the more popular saloons in the Stingaree district. One of the reasons it drew a good crowd was the Golden Poppy brothel upstairs. Owned by Madam Cora, each room was painted a different color, like emerald green, summer yellow, or ruby red, and each prostitute was required to dress in matching garments.

Wyatt had a long-standing interest in boxing and horse racing. He refereed boxing matches in San Diego, Tijuana, and San Bernardino. In the 1887 San Diego City Directory he was listed as a capitalist or gambler. He won his first race horse “Otto Rex” in a card game and began investing in racehorses. He also judged prize fights on both sides of the border and raced horses. Earp was one of the judges at the County Fair horse races held in Escondido in 1889. As rapidly as the boom started, it came to an end, and the population of San Diego fell from a high of 40,000 in 1885 when Earp arrived to only 16,000 in 1890.

On July 3, 1888, Mattie Blaylock, who had always considered herself Wyatt’s wife, committed suicide in Pinal, Arizona Territory, by taking an overdose of laudanum.

Move to San Francisco

The Earps moved back to San Francisco in 1891 so Josie could be closer to her family. Earp developed a reputation as a sportsman as well as a gambler. He held onto his San Diego properties but their value fell, but he could not pay the taxes and was forced to sell the lots. He continued to race horses, but by 1896 he could not longer afford to own them but raced them on behalf of the owner of a horse stable in Santa Rosa that he managed for her. From 1891 to 1897, they lived in at least four different locations in the city: 145 Ellis St., 720 McAllister St., 514A Seventh Ave. and 1004 Golden Gate Ave.

Their relationship was at times tempestuous. Wyatt had a mischievous sense of humor. He knew his wife preferred Josephine and detested “Sadie”, but early in their relationship he began calling her ‘Sadie’. Josephine gambled to excess and Wyatt had affairs. Josephine later developed a reputation as a shrew who made life difficult for Earp.

In Santa Rosa, Earp personally competed in and won a harness race. Josephine wrote in I Married Wyatt Earp: The Recollections of Josephine Sarah Marcus, that she and Wyatt were married in 1892 by the captain of multimillionaire Lucky Baldwin’s yacht aboard his yacht. Raymond Nez wrote that his grandparents witnessed their marriage aboard a yacht off the California coast. No public record of their marriage has ever been found. Baldwin also owned the Santa Anita racetrack, which Wyatt–a long-time horse aficionado–frequented when they were in Los Angeles.

Fixes Fitzsimmons-Sharkey fight

On December 2, 1896, Earp was a last-minute choice as referee for a boxing match that the promoters billed as the heavyweight championship of the world. Bob Fitzsimmons was set to fight Tom Sharkey that night at the Mechanics’ Pavilion in San Francisco. Earp had refereed 30 or so matches in earlier days, though not under the Marquis of Queensbury rules, but under the older and more liberal London Prize Ring Rules. The fight may have been the most anticipated fight on American soil that year. Fitzsimmons was favored to win, and bets flowed heavily his way.

Fitzsimmons dominated Sharkey throughout the fight, and in the eighth round, he hit Sharkey with his famed “solar plexus punch”, an uppercut under the heart that could render a man temporarily helpless. Fitzsimmons’ next punch apparently caught Sharkey below the belt and Sharkey dropped, clutched his groin, and rolled on the canvas, screaming foul. Wyatt stopped the bout, ruling that Fitzsimmons had hit Sharkey below the belt, but virtually no one witnessed the punch. Earp awarded the fight to Sharkey, who attendants carried out as “limp as a rag”. The 15,000 fans in attendance greeted his decision with loud boos and catcalls. It was widely believed that there had been no foul and Earp had bet on Sharkey. While several doctors verified afterward that Sharkey had been hit hard below the belt, the public had bet heavily on Fitzsimmons and they were livid at the outcome.

Fitzsimmons went to court to overturn Earp’s decision. Newspaper accounts and testimony over the next two weeks revealed a conspiracy among the boxing promoters to fix the fight’s outcome.

Stories about the fight and Earp’s contested decision were distributed nationwide to a public that until that time knew little of Wyatt Earp. Earp was parodied in editorial cartoon caricatures and vilified in newspaper stories across the United States.

On December 17, Judge Sanderson finally ruled that prize fighting was illegal in San Francisco and the courts would not determine who the winner was. Sharkey retained the purse, but the decision provided no vindication for Earp. Until the fight, Earp had been a minor figure known regionally in California and Arizona. Afterward, his name was known from coast to coast in the worst possible way. Earp sold his interest in his horses on December 20 and left San Francisco shortly afterward. He only returned when he caught a boat to Alaska. Earp’s decision left a smear on his public character that followed him until he died and afterward.

Eight years later, Dr. B. Brookes Lee was arrested in Portland, Oregon. He had been accused of treating Sharkey to make it appear that he had been fouled by Fitzsimmons. Lee admitted it was true. “I fixed Sharkey up to look as if he had been fouled. How? Well, that is something I do not care to reveal, but I will assert that it was done–that is enough. There is no doubt that Fitzsimmons was entitled to the decision and did not foul Sharkey. I got $1,000 for my part in the affair.”