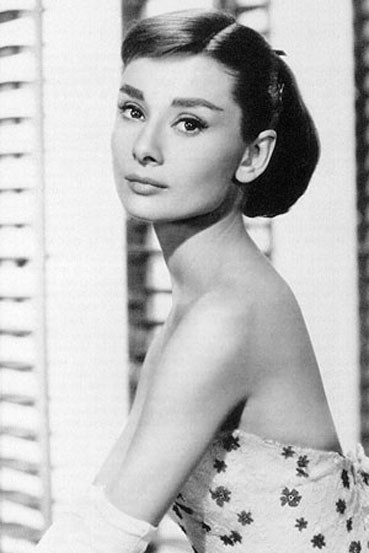

Audrey Hepburn (/’?:dri ‘h?p?b?rn/; born Audrey Kathleen Ruston; 4 May 1929 – 20 January 1993) was a British actress and humanitarian. Recognised as a film and fashion icon, Hepburn was active during Hollywood’s Golden Age. She was ranked by the American Film Institute as the third greatest female screen legend in the history of American cinema and has been placed in the International Best Dressed List Hall of Fame. She is also regarded by some to be the most naturally beautiful woman of all time.

Born in Ixelles, a district of Brussels, Hepburn spent her childhood between Belgium, England and the Netherlands, including German-occupied Arnhem during the Second World War. In Amsterdam, she studied ballet with Sonia Gaskell before moving to London in 1948 to continue her ballet training with Marie Rambert and perform as a chorus girl in West End musical theatre productions. She spoke several languages including English, French, Dutch, Italian, Spanish, and German.

After appearing in several British films and starring in the 1951 Broadway play Gigi, Hepburn played the lead role in Roman Holiday (1953), for which she was the first actress to win an Academy Award, a Golden Globe and a BAFTA Award for a single performance. The same year, she won a Tony Award for Best Lead Actress in a Play for Ondine. She went on to star in a number of successful films, such as Sabrina (1954), The Nun’s Story (1959), Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961), Charade (1963), My Fair Lady (1964) and Wait Until Dark (1967), for which she received Academy Award, Golden Globe and BAFTA nominations. Hepburn remains one of few people who have won Academy, Emmy, Grammy, and Tony Awards. She won a record three BAFTA Awards for Best British Actress in a Leading Role.

She appeared in fewer films as her life went on, devoting much of her later life to UNICEF. Although contributing to the organisation since 1954, she worked in some of the most profoundly disadvantaged communities of Africa, South America and Asia between 1988 and 1992. She was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in recognition of her work as a UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador in December 1992. A month later, Hepburn died of appendiceal cancer at her home in Switzerland at the age of 63.

Early life

Audrey Hepburn was born Audrey Kathleen Ruston on 4 May 1929 at number 48 Rue Keyenveld in Ixelles, a municipality in Brussels, Belgium. Her father, Joseph Victor Anthony Ruston (1889-1980), was a British subject born in Ú?ice, Bohemia, to Anna Ruston (née Wels), of Austrian descent, and Victor John George Ruston, of British and Austrian descent. A one-time honorary British consul in the Dutch East Indies, Ruston had earlier been married to Cornelia Bisschop, a Dutch heiress. Although born Ruston, he later double-barrelled the surname to the more “aristocratic” Hepburn-Ruston, mistakenly believing himself descended from James Hepburn, third husband of Mary, Queen of Scots.

Her mother, Baroness Ella van Heemstra (1900-1984), was a Dutch aristocrat and the daughter of Baron Aarnoud van Heemstra, who was mayor of Arnhem from 1910 to 1920 and served as Governor of Dutch Suriname from 1921 to 1928. Ella’s mother was Elbrig Willemine Henriette, Baroness van Asbeck (1873-1939), who was a granddaughter of jurist Dirk van Hogendorp. At age nineteen, Ella had married Jonkheer (Esquire) Hendrik Gustaaf Adolf Quarles van Ufford, but they divorced in 1925. Hepburn had two half-brothers from this marriage who were both born in the Dutch East Indies: Jonkheer Arnoud Robert Alexander Quarles van Ufford (1920-1979) and Jonkheer Ian Edgar Bruce Quarles van Ufford (1924-2010). Ella, Baroness van Heemstra, was named Dame of the Most Venerable Order of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem by Queen Elizabeth II on 7 September 1971.

Ruston and van Heemstra married in the Dutch-Colonial Batavia, Dutch East Indies in September 1926. They moved back to Europe, to Ixelles in Belgium, where Hepburn was born in 1929. In January 1932 the family moved on to Linkebeek, a nearby Brussels municipality. Although born in Belgium, Hepburn held British citizenship through her father.

Because of her mother’s family in the Netherlands and her father’s British background and job with a British company, the family often travelled among the three countries. With her multinational background, she went on to speak five languages; she picked up French, Spanish and Italian in addition to her native English and Dutch. Hepburn participated in ballet by the age of 5.

© Image credit

Childhood and adolescence during World War II

Hepburn’s parents were members of the British Union of Fascists in the mid-1930s, with her father becoming a true Nazi sympathiser. The marriage began to fail from 1935, and after her mother discovered him in bed with the nanny of her children, Hepburn’s father left the family abruptly. Joseph settled in London following the divorce. In the 1960s, Hepburn would finally locate him again in Dublin through the Red Cross. Although he remained emotionally detached, his daughter remained in contact and supported him financially until his death.

In 1937, Ella and Audrey moved to Kent, South East England, where Hepburn was educated at a tiny independent school in Elham, run by two sisters known as “The Mesdamoiselles Smith”; the school was attended by about 14 children. In September 1939, Britain declared war on Germany, and Hepburn’s mother relocated with her daughter back to Arnhem, in the belief that (as during World War I) the Netherlands would remain neutral and be spared a German attack. Whilst there, Hepburn attended the Arnhem Conservatory from 1939 to 1945 where, in addition to the standard school curriculum, she trained in ballet with Winja Marova. After the Germans invaded the Netherlands in 1940, Hepburn adopted the pseudonym Edda van Heemstra, because an “English sounding” name was considered dangerous during the German occupation. In 1942, Hepburn’s uncle, Otto van Limburg Stirum (husband of her mother’s older sister, Miesje), was executed in retaliation for an act of sabotage by the resistance movement, while Hepburn’s half brother Ian was deported to Berlin to work in a German labour camp. Hepburn’s other half-brother Alex went into hiding to avoid the same fate.

After this, Ella, Miesje, and Hepburn moved in with Baron Aarnoud van Heemstra in nearby Velp. During her wartime struggles, Hepburn suffered from malnutrition, developed acute anæmia, respiratory problems, and edema. Hepburn, in a retrospective interview, commented, “I have memories. More than once I was at the station seeing trainloads of Jews being transported, seeing all these faces over the top of the wagon. I remember, very sharply, one little boy standing with his parents on the platform, very pale, very blond, wearing a coat that was much too big for him, and he stepped on to the train. I was a child observing a child.”

By 1944, Hepburn had become a proficient ballet dancer. She had secretly danced for groups of people to collect money for the Dutch resistance. “The best audience I ever had made not a single sound at the end of my performances”, she remarked. She also occasionally acted as a courier for the resistance, delivering messages and packages. After the Allied landing on D-Day, living conditions grew worse and Arnhem was subsequently devastated in the fighting during Operation Market Garden. During the Dutch famine that followed in the winter of 1944, the Germans had blocked the resupply routes of the Dutch already-limited food and fuel supplies as retaliation for railway strikes that were held to hinder German occupation. People starved and froze to death in the streets; Hepburn and many others resorted to making flour out of tulip bulbs to bake cakes and biscuits. One way young Audrey passed the time was by drawing; some of her childhood artwork can be seen today. When the country was liberated, United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration trucks followed. Hepburn said in an interview that she fell ill from putting too much sugar in her porridge and eating an entire can of condensed milk. Hepburn’s war-time experiences sparked her devotion to UNICEF, an international humanitarian organisation, in her later career.

© Image credit

Career beginnings and early roles

After the war ended in 1945, Ella and Audrey moved to Amsterdam, where Hepburn took ballet lessons for three years with Sonia Gaskell, a leading figure in Dutch ballet. In 1948, she appeared for the first time on film, as an air stewardess in an educational travel film made by Charles van der Linden and Henry Josephson, Dutch in Seven Lessons. She moved to study at the Ballet Rambert; supporting herself with part-time work as a model, and dropping “Ruston” from her surname. On requesting Rambert’s assessment of her prospects, Hepburn was told she had talent, but her height and weak constitution (the after effect of wartime undernutrition) would make the status of prima ballerina unattainable. She decided to concentrate on acting.

Hepburn’s mother worked menial jobs in order to support them but Hepburn needed to find employment. Since she had trained in theatre all her life, working as a London chorus girl seemed sensible. “I needed the money; it paid ?3 more than ballet jobs.” She performed in the musical theatre revues High Button Shoes (1948) at the London Hippodrome and Cecil Landeau’s Sauce Tartare (1949) and Sauce Piquante (1950) at the Cambridge Theatre in the West End. Through her theatrical work, she realised her voice was not strong and needed to be developed; she therefore took elocution lessons with the actor Felix Aylmer. After being spotted by an ABPC casting director in Sauce Piquante, Hepburn registered with the British film studio as a freelance actress while still working in the West End. The unknown Hepburn appeared in minor roles in the 1951 films One Wild Oat, Laughter in Paradise, Young Wives’ Tale and The Lavender Hill Mob before playing her first major supporting role in Thorold Dickinson’s The Secret People (1952), in which she played a prodigious ballerina and performed all of her own dancing sequences.

Hepburn was then offered a small role in the film being shot in both English and French Monte Carlo Baby (Nous Irons à Monte Carlo) (1951). While Hepburn was filming on location, the French novelist Colette happened to be on the set, on an international search for the right actress to play the title character in her Broadway play Gigi. Upon first glance of Hepburn, Colette supposedly whispered, “Voilà”, indicating Hepburn, “there’s your Gigi.” Hepburn supplemented her rehearsals with hours of private coaching. On 24 November 1951, Gigi opened at the Fulton Theatre and Hepburn’s name was hoisted above the title of the play on the theatre marquee. The play ran for 219 performances, and finished on 31 May 1952. This debut on Broadway earned Hepburn a Theatre World Award. She also reprised this role in the US tour of the play which began 13 October 1952 in Pittsburgh and visited Cleveland, Chicago, Detroit, Washington and Los Angeles before closing on 16 May 1953 in San Francisco.

Roman Holiday and stardom

In the Italian-set Roman Holiday (1953), Hepburn had her first starring role as Princess Anne, an incognito European princess who, escaping the reins of royalty, falls in love with an American newsman (Gregory Peck). While producers initially wanted Elizabeth Taylor for the role, director William Wyler was so impressed by Hepburn’s screen test that he cast her in the lead. Wyler later commented, “She had everything I was looking for: charm, innocence, and talent. She also was very funny. She was absolutely enchanting and we said, ‘That’s the girl!'”

Originally, the film was to have had only Gregory Peck’s name above its title, with “Introducing Audrey Hepburn” beneath in smaller font. However, Peck suggested to Wyler that he elevate her to equal billing so that her name appeared before the title and in type as large as his: “You’ve got to change that because she’ll be a big star and I’ll look like a big jerk.”

Hepburn garnered critical and commercial acclaim for her portrayal, adding to her unexpected Academy Award for Best Actress, her first BAFTA Award for Best British Actress in a Leading Role, and only Golden Globe Award for Best Actress – Motion Picture Drama in 1953. In his review in The New York Times, A. H. Weiler wrote:

Although she is not precisely a newcomer to films Audrey Hepburn, the British actress who is being starred for the first time as Princess Anne, is a slender, elfin and wistful beauty, alternately regal and childlike in her profound appreciation of newly-found, simple pleasures and love. Although she bravely smiles her acknowledgement of the end of that affair, she remains a pitifully lonely figure facing a stuffy future.

Hepburn was signed to a seven-picture contract with Paramount with 12 months in between films to allow her time for stage work while spawning what became known as the Audrey Hepburn “look” after her illustration was placed on the 7 September 1953 cover of TIME magazine.

Following her success in Roman Holiday, she starred in Billy Wilder’s romantic Cinderella-story comedy Sabrina (1954), in which wealthy brothers (Humphrey Bogart and William Holden) compete for the affections of their chauffeur’s innocent daughter (Hepburn). For her performance, she was nominated for the 1954 Academy Award for Best Actress while winning the BAFTA Award for Best Actress in a Leading Role the same year. Bosley Crowther of The New York Times wrote:

One might guess this is Miss Hepburn’s picture, since she has the title role and has come to it trailing her triumphs from last year’s “Roman Holiday”. And, indeed, she is wonderful in it–a young lady of extraordinary range of sensitive and moving expressions within such a frail and slender frame. She is even more luminous as the daughter and pet of the servants’ hall than she was as a princess last year, and no more than that can be said.

She began another collaboration that year, this time with actor Mel Ferrer, starred in the fantasy play Ondine on Broadway. With her lithe and lean frame, Hepburn made a convincing water spirit named Ondine in this sad story about love found and lost with a human (Ferrer). A New York Times critic commented:

Somehow Miss Hepburn is able to translate [its intangibles] into the language of the theatre without artfulness or precociousness. She gives a pulsing performance that is all grace and enchantment, disciplined by an instinct for the realities of the stage.

Hepburn and Ferrer married on 25 September 1954, in Switzerland; their sometimes tumultuous partnership would last for the better part of the next 15 years. Her performance won her the 1954 Tony Award for Best Performance by a Leading Actress in a Play the same year she won the Academy Award for Roman Holiday. Hepburn, therefore, stands as one of three actresses to receive the Academy and Tony Awards for Best Actress in the same year (the other two are Shirley Booth and Ellen Burstyn).

Hepburn received the Golden Globe for World Film Favorite – Female in 1955, and also became a major fashion influence.

Hepburn was asked to play Anne Frank in both the Broadway and film adaptations of Frank’s life. Hepburn, however, who was born the same year as Frank, found herself “emotionally incapable” of the task, and at almost 30 years old, too old. The role was eventually given to Susan Strasberg and Millie Perkins in the play and film respectively.

Having become one of Hollywood’s most popular box-office attractions, she went on to star in a series of successful films during the remainder of the decade, including her BAFTA- and Golden Globe-nominated role as Natasha Rostova in War and Peace (1956), an adaptation of the Tolstoy novel set during the Napoleonic wars with Henry Fonda and husband Mel Ferrer. In 1957, she exhibited her dancing abilities in her debut musical film Funny Face (1957) where Fred Astaire, a fashion photographer, discovers a beatnik bookstore clerk (Hepburn), who, lured by a free trip to Paris, becomes a beautiful model. The same year Hepburn starred in another romantic comedy, Love in the Afternoon, alongside Gary Cooper and Maurice Chevalier.

She played Sister Luke in The Nun’s Story (1959), which focuses on the character’s struggle to succeed as a nun, alongside co-star Peter Finch. The role produced a third Academy Award nomination for Hepburn and earned her a second BAFTA Award. A review in Variety read, “Hepburn has her most demanding film role, and she gives her finest performance.” Films in Review stated that her performance “will forever silence those who have thought her less an actress than a symbol of the sophisticated child/woman. Her portrayal of Sister Luke is one of the great performances of the screen.” Reportedly, she spent hours in convents and with members of the Church to bring truth to her portrayal: “I gave more time, energy and thought to this than to any of my previous screen performances.”

Following this, she received lukewarm reception for starring with Anthony Perkins in the romantic adventure Green Mansions (1959) where she plays–“with grace and dignity”–the “ethereal” Rima, a jungle girl, who falls in love with a Venezuelan traveler played by Perkins, and The Unforgiven (1960), her only western film, where she appears “a bit too polished, too fragile and civilized among such tough and stubborn types” of Burt Lancaster and Lillian Gish in a story of racism against a group of Native Americans.

Breakfast at Tiffany’s and iconic role

Three months after the birth of her son, Sean, in 1960, Hepburn began work on Blake Edwards’ Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961), a film loosely based on the Truman Capote novella. The film was drastically changed from the book. Capote disapproved of many changes and proclaimed that Hepburn was “grossly miscast” as Holly Golightly, a quirky New York call girl, a role he had envisioned for Marilyn Monroe. Hepburn’s portrayal of Golightly was adapted from the original: “I can’t play a hooker”, she admitted to Marty Jurow, co-producer of the film.

Despite the sanitisation and resulting lack of sexual innuendo in her character, her portrayal was nominated for the 1961 Academy Award for Best Actress and became an iconic character in American cinema. Often considered her defining role, Hepburn’s high fashion style and sophistication as Holly Golightly within the film became synonymous with her. She named the role “the jazziest of my career” yet admitted: “I’m an introvert. Playing the extroverted girl was the hardest thing I ever did.” The little black dress which is worn by Hepburn in the beginning of the film is cited as one of the most iconic items of clothing in the history of the twentieth century and perhaps the most famous little black dress of all time.

Playing opposite Shirley MacLaine and James Garner, her next role in William Wyler’s lesbian-themed drama The Children’s Hour (1961) saw Hepburn and MacLaine play teachers whose lives become troubled after a student accuses them of being lesbians. Due to the social mores of the time, the film and Hepburn’s performance went largely unmentioned, both critically and commercially. Bosley Crowther of The New York Times, opined that the film “is not too well acted” with the exception of Hepburn who “gives the impression of being sensitive and pure” of its “muted theme”, while Variety magazine also complimented Hepburn’s “soft sensitivity, mar-velous [sic] projection and emotional understatement” adding that Hepburn and MacLaine “beautifully complement each other”.

Her only film with Cary Grant came in the comic thriller Charade (1963). Hepburn, who plays Regina Lampert, finds herself pursued by several men who chase the fortune her murdered husband had stolen. The role earned her third and final competitive BAFTA Award and accrued another Golden Globe nomination though critic Bosley Crowther was less kind: “Hepburn is cheerfully committed to a mood of how-nuts-can-you-be in an obviously comforting assortment of expensive Givenchy costumes.” Grant (59 years old at the time), who had previously withdrawn from the starring male lead roles in Roman Holiday and Sabrina, was sensitive about the age difference between Hepburn (at age 34) and him, making him uncomfortable about the romantic interplay. To satisfy his concerns, the filmmakers agreed to change the screenplay so that Hepburn’s character would be the one to romantically pursue his. Grant, however, loved to humour Hepburn and once said, “All I want for Christmas is another picture with Audrey Hepburn.”

Paris When It Sizzles (1964) reteamed Hepburn with William Holden nearly ten years after Sabrina. The Parisian-set screwball comedy, called “marshmallow-weight hokum”, was “uniformly panned” but critics were kind to Hepburn’s creation of Gabrielle Simpson, the young assistant of a Hollywood screenwriter (Holden) who aids his writer’s block by acting out his fantasies of possible plots, describing her as “a refreshingly individual creature in an era of the exaggerated curve.” Critical reception was worsened by a number of problems that plagued the set behind the scenes. Holden tried, without success, to rekindle a romance with the now-married actress; that, combined with his alcoholism made the situation a challenge. Hepburn, after principal photography began, demanded the dismissal of cinematographer Claude Renoir after seeing what she felt were unflattering dailies. Superstitious, she also insisted on dressing room 55 because that was her lucky number (she had dressing room 55 for Roman Holiday and Breakfast at Tiffany’s) and required that Givenchy, her long-time designer, be given a credit in the film for her perfume.

“Not since Gone with the Wind has a motion picture created such universal excitement as My Fair Lady”, wrote Soundstage magazine in 1964, yet Hepburn’s landing the role of Cockney flower girl Eliza Doolittle in the 1964 George Cukor film adaptation of the stage musical sparked controversy. Julie Andrews, who had originated the role in the stage show, had not been offered the part because producer Jack Warner thought Hepburn or Elizabeth Taylor more “bankable” propositions. Initially refusing, Hepburn asked Warner to give it to Andrews but, eventually, Hepburn was cast.

Further friction was created when, although non-singer Hepburn had sung with “throaty charm” in Funny Face and had lengthy vocal preparation for the role in My Fair Lady, her vocals were dubbed by Marni Nixon. A dubber was required because Eliza Doolittle’s songs were not transposed down to accommodate Hepburn’s “low-mezzo voice” (as Nixon referred to it). Upset, when first informed, she walked out. She returned the next day and apologised to everybody for her “wicked behaviour”. Although Hepburn had lip synced to her recorded tracks during filming, Nixon looped her vocals in post-production and was given multiple attempts to match Hepburn’s lip movements precisely.

Overall, about 90% of her singing was dubbed despite being promised that most of her vocals would be used. Hepburn’s voice remains in one line in “I Could Have Danced All Night”, in the first verse of “Just You Wait”, and in the entirety of its reprise in addition to sing-talking in parts of “The Rain in Spain” in the finished film. When asked about the dubbing of an actress with such distinctive vocal tones, Hepburn frowned and said, “You could tell, couldn’t you? And there was Rex, recording all his songs as he acted … next time –” She bit her lip to prevent her saying more. She later admitted that she would have never accepted the role knowing that Warner intended to have nearly all of her singing dubbed.

The controversy reached its height when, despite the film’s accumulation of eight out of a possible twelve awards at the 37th Academy Awards, Hepburn was left nomination-less in the Best Actress category. Andrews would be nominated for her efforts in Mary Poppins (1964), and won. The media tried to play up a rivalry between the two women, although both denied any such thing, and got along well. Despite such strife, many critics greatly applauded Hepburn’s “exquisite” performance. “The happiest thing about [ My Fair Lady]”, wrote Bosley Crowther in The New York Times “is that Audrey Hepburn superbly justifies the decision of Jack Warner to get her to play the title role.” Her co-star Rex Harrison, who played Professor Higgins, also called Hepburn his favourite leading lady and Gene Ringgold of Soundstage also commented that “Audrey Hepburn is magnificent. She is Eliza for the ages”, while adding, “Everyone agreed that if Julie Andrews was not to be in the film, Audrey Hepburn was the perfect choice.”

As the decade carried on, Hepburn appeared in an assortment of genres including the heist comedy How to Steal a Million (1966) where she played Nicole, the daughter of a famous art collector whose collection consists entirely of forgeries. Fearing her father’s exposure, Nicole sets out to steal one of his priceless statues with the help of Simon Dermott (Peter O’Toole). In 1967, she starred in two films; the first being Two for the Road, a non-linear and innovative British dramedy that traces the course of a couple’s troubled marriage. Director Stanley Donen said that Hepburn was more free and happy than he had ever seen her, and he credited that to co-star Albert Finney.

The second, Wait Until Dark, is a suspense thriller in which Hepburn demonstrated her acting range by playing the part of a terrorised blind woman. Filmed on the brink of her divorce, it was a difficult film considering husband Mel Ferrer was its producer. She lost fifteen pounds under the stress, but she found solace in co-star Richard Crenna and director Terence Young. Hepburn earned her fifth and final competitive Academy Award nomination for Best Actress; Bosley Crowther affirmed, “Hepburn plays the poignant role, the quickness with which she changes and the skill with which she manifests terror attract sympathy and anxiety to her and give her genuine solidity in the final scenes.”

Final projects

From 1967 onward, after fifteen highly successful years in film, Hepburn decided to devote more time to her family and acted only occasionally. She attempted a comeback in 1976, co-starring with Sean Connery, in the period piece Robin and Marian, which was moderately successful. In 1979, Hepburn took the lead role of Elizabeth Roffe in the international production of Bloodline, re-teaming with director Terence Young ( Wait Until Dark). She shared top billing with co-stars Ben Gazzara, James Mason and Romy Schneider. Author Sidney Sheldon revised his novel when it was reissued to tie into the film, making her character a much older woman to better match the actress’s age. The film, an international intrigue amid the jet-set, was a critical and box office failure.

Hepburn’s last starring role in a cinematic film was with Gazzara in the 1981 comedy They All Laughed, directed by Peter Bogdanovich. The film was overshadowed by the murder of one of its stars, Bogdanovich’s girlfriend, Dorothy Stratten; the film was released after Stratten’s death but only in limited runs. In 1987, she co-starred with Robert Wagner in a tongue-in-cheek made-for-television caper film, Love Among Thieves, which borrowed elements from several of Hepburn’s films, most notably Charade and How to Steal a Million.

After finishing her last role in a motion picture in 1988, a cameo appearance as an angel in Steven Spielberg’s Always, Hepburn completed only two more entertainment-related projects, both critically acclaimed. Gardens of the World with Audrey Hepburn was a PBS documentary television series, her final performance before cameras filmed on location in seven countries in the spring and summer of 1990. A one-hour special preceded the series, debuting in March 1991, while the series commenced the day after her death (21 January 1993). For the series’s debut, Hepburn was posthumously awarded the 1993 Emmy Award for Outstanding Individual Achievement – Informational Programming. Recorded in 1992, her spoken word album, Audrey Hepburn’s Enchanted Tales, features readings of classic children’s stories and earned her a posthumous Grammy Award for Best Spoken Word Album for Children. She remains one of the few entertainers to win Grammy and Emmy Awards posthumously.

Humanitarian career

Hepburn was appointed Goodwill Ambassador of UNICEF. United States president George H. W. Bush presented her with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in recognition of her work with UNICEF, and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences posthumously awarded her the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award for her contribution to humanity, with her son accepting on her behalf. Grateful for her own good fortune after enduring the German occupation as a child, she dedicated the remainder of her life to helping impoverished children in the poorest nations. Hepburn’s travels were made easier by her wide knowledge of languages; besides being naturally bilingual in English and Dutch, she also was fluent in French, Italian, Spanish, and German.

Though she had done work for UNICEF in the 1950s, starting in 1954 with radio presentations, this was a much higher level of dedication. Her family say that the thoughts of dying, helpless children consumed her for the rest of her life. In 2002, at the United Nations Special Session on Children, UNICEF honoured Hepburn’s legacy of humanitarian work by unveiling a statue, “The Spirit of Audrey”, at UNICEF’s New York headquarters. Her service for children is also recognised through the U.S. Fund for UNICEF’s Audrey Hepburn Society.

1988-1989

Hepburn’s first field mission for UNICEF was to Ethiopia in 1988. She visited an orphanage in Mek’ele that housed 500 starving children and had UNICEF send food. Of the trip, she said, “I have a broken heart. I feel desperate. I can’t stand the idea that two million people are in imminent danger of starving to death, many of them children, [and] not because there isn’t tons of food sitting in the northern port of Shoa. It can’t be distributed. Last spring, Red Cross and UNICEF workers were ordered out of the northern provinces because of two simultaneous civil wars… I went into rebel country and saw mothers and their children who had walked for ten days, even three weeks, looking for food, settling onto the desert floor into makeshift camps where they may die. Horrible. That image is too much for me. The ‘Third World’ is a term I don’t like very much, because we’re all one world. I want people to know that the largest part of humanity is suffering.”

In August 1988, Hepburn went to Turkey on an immunisation campaign. She called Turkey “the loveliest example” of UNICEF’s capabilities. Of the trip, she said, “the army gave us their trucks, the fishmongers gave their wagons for the vaccines, and once the date was set, it took ten days to vaccinate the whole country. Not bad.” In October, Hepburn went to South America. In Venezuela and Ecuador, Hepburn told the United States Congress, “I saw tiny mountain communities, slums, and shantytowns receive water systems for the first time by some miracle – and the miracle is UNICEF. I watched boys build their own schoolhouse with bricks and cement provided by UNICEF.”

Hepburn toured Central America in February 1989, and met with leaders in Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala. In April, she visited Sudan with Wolders as part of a mission called “Operation Lifeline”. Because of civil war, food from aid agencies had been cut off. The mission was to ferry food to southern Sudan. Hepburn said, “I saw but one glaring truth: These are not natural disasters but man-made tragedies for which there is only one man-made solution – peace.” In October, Hepburn and Wolders went to Bangladesh. John Isaac, a UN photographer, said, “Often the kids would have flies all over them, but she would just go hug them. I had never seen that. Other people had a certain amount of hesitation, but she would just grab them. Children would just come up to hold her hand, touch her – she was like the Pied Piper.”

1990-1992

In October 1990, Hepburn went to Vietnam in an effort to collaborate with the government for national UNICEF-supported immunisation and clean water programmes.

In September 1992, four months before she died, Hepburn went to Somalia. Calling it “apocalyptic”, she said, “I walked into a nightmare. I have seen famine in Ethiopia and Bangladesh, but I have seen nothing like this – so much worse than I could possibly have imagined. I wasn’t prepared for this.” “The earth is red – an extraordinary sight – that deep terracotta red. And you see the villages, displacement camps and compounds, and the earth is all rippled around these places like an ocean bed and I was told these were the graves. There are graves everywhere. Along the road, wherever there is a road, around the paths that you take, along the riverbeds, near every camp – there are graves everywhere.”

Though scarred by what she had seen, Hepburn still had hope. “Taking care of children has nothing to do with politics. I think perhaps with time, instead of there being a politicisation of humanitarian aid, there will be a humanisation of politics.” “Anyone who doesn’t believe in miracles is not a realist. I have seen the miracle of water which UNICEF has helped to make a reality. Where for centuries young girls and women had to walk for miles to get water, now they have clean drinking water near their homes. Water is life, and clean water now means health for the children of this village.” “People in these places don’t know Audrey Hepburn, but they recognise the name UNICEF. When they see UNICEF their faces light up, because they know that something is happening. In the Sudan, for example, they call a water pump UNICEF.”

© Image credit

Marriages, relationships and children

In 1952, Hepburn was engaged to the young James Hanson, whom she had known since her London dancing days. She called it “love at first sight”; however, after having her wedding dress fitted and the date set, she decided the marriage would not work because the demands of their careers would keep them apart most of the time. She issued a statement about her decision, saying, “When I get married, I want to be really married.” In the early 1950s, she also dated future Hair producer Michael Butler.

Hepburn and Gregory Peck bonded during the filming of Roman Holiday (1953) and there were rumours that they were romantically involved; both denied it. Hepburn, however, added, “Actually, you have to be a little bit in love with your leading man and vice versa. If you’re going to portray love, you have to feel it. You can’t do it any other way. But you don’t carry it beyond the set.” They did however become lifelong friends. During the filming of Sabrina (1954), Hepburn and the already-married William Holden became romantically involved. She hoped to marry him and have children, but she broke off the relationship when Holden revealed that he had undergone a vasectomy. Although a common perception that Bogart and Hepburn (both starred in Sabrina together) did not get along, Hepburn commented that, “Sometimes it’s the so-called ‘tough guys’ that are the most tender hearted, as Bogey was with me.”

At a cocktail party hosted by Gregory Peck, Hepburn met American actor Mel Ferrer. Ferrer recalled that, “We began talking about theatre; she knew all about the La Jolla Playhouse Summer Theatre, where Greg Peck and I had been co-producing plays. She also said she’d seen me three times in the movie Lili. Finally, she said she’d like to do a play with me, and she asked me to send her a likely play if I found one.” Ferrer, vying for Hepburn to take the title role, sent her the script for the play Ondine. She agreed and rehearsals started in January 1954. Eight months later, on 25 September 1954, after meeting, working together, and falling in love, the pair were married in Bürgenstock while preparing to star together in the film War and Peace (1955).

Before having their only son, Hepburn had two miscarriages — one in March 1955 and another in 1959. The latter occurred when filming The Unforgiven (1960) where breaking her back after falling off a horse and onto a rock resulted in hospital stay and miscarriage induced by physical and mental stress. Hepburn took a year off work in order to carry a child to term. Sean Hepburn Ferrer, their son, whose godfather was the novelist A. J. Cronin, who resided near Hepburn in Lucerne, was born on 17 July 1960.

Despite the insistence from gossip columns that their marriage would not last, Hepburn claimed that she and Ferrer were inseparable and happy together, though she admitted that he had a bad temper. Ferrer was rumoured to be too controlling of Hepburn and had been referred to by others as being her “Svengali” – an accusation that Hepburn laughed off. William Holden was quoted as saying, “I think Audrey allows Mel to think he influences her.” Hepburn had another two miscarriages later, in 1965 and 1967. After a 14-year marriage, the couple divorced on 5 December 1968. Their son believed that Hepburn had stayed in the marriage too long.

In June 1968 she was invited on a cruise by Princess Olimpia Emmanuela Torlonia di Civitella-Cesi and her industrialist husband Paul-Annik Weiller (1933-1998). On the cruise she met the Italian psychiatrist Andrea Dotti and fell in love with him on a trip to the Greek ruins. She believed she would have more children, and possibly stop working. She married him on 18 January 1969 at age 39, and gave birth to their son Luca Dotti on 8 February 1970. While pregnant with Luca in 1969, Hepburn was more careful, resting for months and passing the time by painting before delivering him by caesarean section. Hepburn tried for another child, but again had a miscarriage, in 1974.

Although Dotti loved Hepburn and was well-liked by Sean, who called him “fun”, he began having affairs with younger women. Hepburn had a romantic relationship with actor Ben Gazzara during the filming of the 1979 movie Bloodline. The Dotti-Hepburn marriage lasted thirteen years and ended in 1982 when Hepburn felt Luca and Sean were old enough to handle life with a single mother. Although Hepburn broke off contact with Ferrer, and only spoke to him two more times during the remainder of her life, she remained in touch with Dotti for the benefit of Luca. On September 30, 2007, Andrea Dotti died after complications from a colonoscopy.

From 1980 until her death, Hepburn lived with and was romantically involved with Dutch actor Robert Wolders, the widower of actress Merle Oberon. She met Wolders through a friend in the later stage of her marriage to Dotti. The divorce from Dotti finalised, Wolders and Hepburn started their lives together, although they never married. In 1989, she called the nine years she had spent with him the happiest years of her life. “Took me long enough”, she said in an interview with American journalist Barbara Walters. Walters then asked why they never married; Hepburn replied that they were married, just not formally.

© Image credit

Illness

Upon return from Somalia to Switzerland in late September 1992, Hepburn began suffering from abdominal pains. She went to specialists and received inconclusive results, so she decided to have herself examined while on a trip to Los Angeles in October. On 1 November Hepburn checked in at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center with her family. Doctors performed a laparoscopy and discovered abdominal cancer that had spread from her appendix, a rare form of cancer belonging to a group of cancers known as pseudomyxoma peritonei (PMP). Having grown slowly over several years, the cancer had metastasised, not as a tumour, but as a thin coating over her small intestine. After surgery, the doctors put Hepburn through 5-fluorouracil Leucovorin chemotherapy. A few days later, she had an obstruction and medication was not enough to dull the pain. She underwent further surgery on December 1. After one hour, the surgeon decided that the cancer had spread too far to be removed fully and was inoperable.

After coming to terms with the gravity of Hepburn’s illness, her family decided to return home to Switzerland in order to celebrate her last Christmas. Because Hepburn was still recovering from surgery, she was unable to fly on commercial aircraft. Hubert de Givenchy offered to help and arranged for Rachel Lambert “Bunny” Mellon to send her private Gulfstream jet, filled with flowers, to take Hepburn from Los Angeles to Geneva. She spent her last days in hospice care at her home in Tolochenaz, Vaud, Switzerland and occasionally was well enough to take walks in her garden, but gradually became more confined to bed rest as she grew weaker.

© Image credit

Death

On the evening of 20 January 1993, Hepburn died at home in her sleep of appendiceal cancer. After her death, Gregory Peck went on camera and tearfully recited her favourite poem, “Unending Love” by Rabindranath Tagore.

Funeral services were held at the village church of Tolochenaz, Switzerland, on 24 January 1993. Maurice Eindiguer, the same pastor who wed Hepburn and Mel Ferrer and baptised her son Sean in 1960, presided over her funeral while Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan, of UNICEF, delivered a eulogy. Many family members and friends attended the funeral, including her sons, partner Robert Wolders, brother Ian Quarles van Ufford, ex-husbands Andrea Dotti and Mel Ferrer, Hubert de Givenchy, executives of UNICEF, and fellow actors Alain Delon and Roger Moore. Flower arrangements were sent to the funeral by Gregory Peck, Elizabeth Taylor, and the Dutch royal family. The same day as her funeral, Hepburn was interred at the Tolochenaz Cemetery, a small cemetery that sits atop a hill overlooking the village.

Audrey’s son Sean is now patron of the pseudomyxomasurvivor charity dedicated to providing support to patients of the rare cancer she suffered from, pseudomyxoma peritonei and is also the ‘rare disease ambassador’ for 2015 on behalf of European Organisation for Rare Diseases.

© Image credit

Legacy

Audrey Hepburn’s legacy as an actress and a personality has endured long after her death. The American Film Institute named Hepburn third among the Greatest Female Stars of All Time. She stands as one of few entertainers who have won Academy, Emmy, Grammy and Tony Awards. She won a record three BAFTA Awards for Best British Actress in a Leading Role. In her last years, she remained a visible presence in the film world. She received a tribute from the Film Society of Lincoln Center in 1991 and was a frequent presenter at the Academy Awards. She received the BAFTA Lifetime Achievement Award in 1992. She was the recipient of numerous posthumous awards including the 1993 Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award and competitive Grammy and Emmy Awards. She has been the subject of many biographies since her death and the 2000 dramatisation of her life titled The Audrey Hepburn Story which starred Jennifer Love Hewitt and Emmy Rossum as the older and younger Hepburn respectively. The film concludes with footage of the real Audrey Hepburn, shot during one of her final missions for UNICEF.

Hepburn’s image is widely used in advertising campaigns across the world. In Japan, a series of commercials used colourised and digitally enhanced clips of Hepburn in Roman Holiday to advertise Kirin black tea. In the United States, Hepburn was featured in a 2006 Gap commercial which used clips of her dancing from Funny Face, set to AC/DC’s “Back in Black”, with the tagline “It’s Back – The Skinny Black Pant”. To celebrate its “Keep it Simple” campaign, the Gap made a sizeable donation to the Audrey Hepburn Children’s Fund. In 2013, a computer-manipulated representation of Hepburn was used in a television advert for the British chocolate bar Galaxy. On 4 May 2014 Google featured a doodle on its homepage on the occasion of Hepburn’s 85th birthday.

© Image credit

Style

Hepburn earned her place in the International Best Dressed List Hall of Fame in 1961 but her reverence as a fashion icon has continued long since her death, proved by accruing the titles “most beautiful woman of all time” and “most beautiful woman of the 20th century” in polls by Evian and QVC respectively. Despite being far from the Hollywood preference of bosomy actresses like Marilyn Monroe, Martine Carol, Kim Novak and Lana Turner, Hepburn was very feminine by her grace, huge eyes and long legs. Against the gender stereotypes of the time, the natural thickness of her brown eyebrows made her “funny face unforgettable”, reminisced director Billy Wilder. He joked, “This girl…may make bosoms a thing of the past.”

Hepburn redefined glamour with “elfin” features and a gamine waif-like figure that inspired designs by couturier Hubert de Givenchy who is credited for creating her style. Givenchy started designing her dresses since the film Sabrina (1954). He noted that, upon being told that the actress he would be responsible for many outfits for would be “Miss Hepburn”, he had expected Katharine Hepburn. When faced with Audrey, he was initially disappointed and told Hepburn he had little time to spare. Nevertheless, she knew exactly how she wanted to look and asked to view his latest collection. Their collaboration in Sabrina formed a lifelong friendship and partnership; she was often a muse for many of his designs and her style became renowned internationally.

“[Givenchy] gave me a look, a kind, a silhouette. He has always been the best and he stayed the best. Because he kept the spare style that I love. What is more beautiful than a simple sheath made an extraordinary way in a special fabric, and just two earrings?” revealed Hepburn. Givenchy created her outfits for many other films, including Funny Face, Love in the Afternoon, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, Paris When It Sizzles, Charade and How to Steal a Million (in which at one point her character is disguised as a cleaning woman and the male lead, played by Peter O’Toole, remarks that this “gives Givenchy a night off”). The designer was always amazed that, even after thirty five years of collaboration, “her measurements [had] not changed an inch”. Givenchy remained Hepburn’s friend and ambassador, and she his muse, throughout her life. Hepburn observed, “I have many things in common with Hubert. We like the same things.” She agreed to model, on occasions, the creations of her friend. In 1988, when he presented his summer collection in Paris, she said, “Wherever I am in the world, he is always there. He is a man who does not disperse into worldliness. He has time for those he loves.” Givenchy subsequently created a perfume for her titled L’Interdit (French for “Forbidden”).

She equally inspired fashion photographer Richard Avedon, who captured an intentionally overexposed close-up of Hepburn’s face in which only her famous features – her eyes, her eyebrows, and her mouth – are visible. “I am, and forever will be, devastated by the gift of Audrey Hepburn before my camera. I cannot lift her to greater heights. She is already there. I can only record. I cannot interpret her. There is no going further than who she is. She has achieved in herself her ultimate portrait.” One of her many costars, Shirley MacLaine, wrote in her 1996 memoir My Lucky Stars, “[Hepburn] had very rare qualities and I envied her style and taste. I felt clumsy and old fashioned when I was with her.” Hepburn’s fashion styles continue to be popular among women today.

Italian shoe designer Salvatore Ferragamo created a shoe for her and made her ambassador of his fashion house while honouring her in a 1999 exhibition dedicated to the actress titled Audrey Hepburn, a woman, the style. She exercised fashion in her lifetime and continues to influence fashion. Fashion experts affirmed that Hepburn’s longevity as a style icon results from her sticking with a look that suited her: “clean lines, simple yet bold accessories, minimalist palette.”

Although Hepburn enjoyed fashion, she did not place much importance on it, preferring casual and comfortable clothes contrary to her image. In addition, she never considered herself attractive. She stated in a 1959 interview, “you can even say that I hated myself at certain periods. I was too fat, or maybe too tall, or maybe just plain too ugly… you can say my definiteness stems from underlying feelings of insecurity and inferiority. I couldn’t conquer these feelings by acting indecisive. I found the only way to get the better of them was by adopting a forceful, concentrated drive.”

The “little black dress” from Breakfast at Tiffany’s, designed by Givenchy, was sold at a Christie’s auction on 5 December 2006 for £467,200, almost seven times its £70,000 pre-sale estimate. This was the highest price paid for a dress from a film, until it was surpassed by the $4.6 million paid in June 2011 for the Marilyn Monroe “subway dress” from The Seven Year Itch. The proceeds went to the City of Joy Aid charity to aid underprivileged children in India. The head of the charity said, “there are tears in my eyes. I am absolutely dumbfounded to believe that a piece of cloth which belonged to such a magical actress will now enable me to buy bricks and cement to put the most destitute children in the world into schools.” However, the dress auctioned by Christie’s was not the one that Hepburn wore in the film. Of the two dresses that Hepburn did wear, one is held in the Givenchy archives while the other is displayed in the Museum of Costume in Madrid. A subsequent London auction of Hepburn’s film wardrobe in December 2009 raised £270,200, including £60,000 for the black Chantilly lace cocktail gown from How to Steal a Million. Half the proceeds were donated to All Children in School, a joint venture of The Audrey Hepburn Children’s Fund and UNICEF.

External links

- Official website of Hepburn (and the Audrey Hepburn Children’s Fund )

- Audrey Hepburn collected news and commentary at The New York Times

- Works by or about Audrey Hepburn in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Audrey Hepburn at the Internet Movie Database

- Audrey Hepburn at the Internet Broadway Database

- Audrey Hepburn at the TCM Movie Database

- Audrey Hepburn at AllMovie

- Audrey Hepburn Society at the U.S. Fund for UNICEF

- Voguepedia – Audrey Hepburn

- Vanity Fair – The Best Dressed Women of all Time – Audrey Hepburn